Art: Cara Hanley

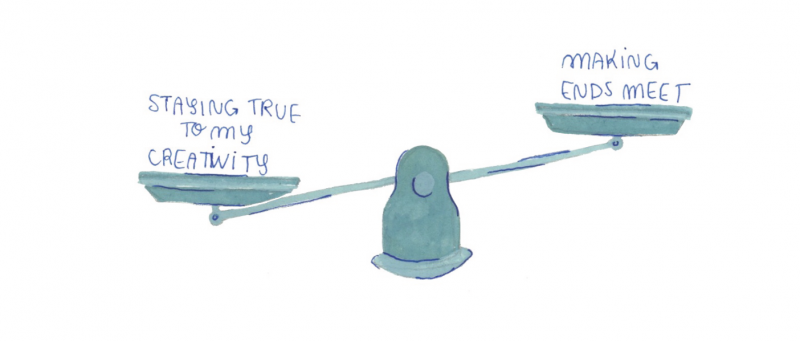

Ask most local creatives in the Capital Region what they do for a living and you will likely get a list of jobs, side hustles and passion projects. More and more it seems, young people (particularly those already working in a creative field) are seeking other projects or becoming entrepreneurs to fulfill their creative drive, pursue interests or pay the bills on time. But this isn’t unique to the area.

Bankrate’s Side Hustle Survey, completed by YouGov Plc in May 2019, collected data from 2,550 working adults with side hustles and found that at least one in three needed the income for living expenses. The study found these workers spent an average of 12 hours per week on side work and made about $1,122 per month. About 40 percent of millennials with a side hustle say it’s the source of at least half their monthly earnings, the survey found. It also found that 27 percent of workers say they’re more passionate about their side gig than their primary job or career.

On sites like Etsy, where more than 2.1 million sellers sold goods in 2018 (up from 1.9 million active sellers in the previous year, according to Statistica), artists are finding ways to make significant money.

But most local artists are not seeking side gigs for the cash. Instead, many are looking for creative release. To see some return for the money, time and energy spent, some manage their own websites, while other artists stick with social media sites like Instagram, where they advertise their creative abilities or post their work, accepting cash or Venmo transactions for their art.

Ariel Einbinder, 29, works full time at Ekologic in Troy, a cashmere clothing and accessory shop that uses 99 percent recycled material to make collaged sweaters, hats, scarves, gloves and more. Einbinder works in garment construction and runs the company’s social media and website, providing the product and staff photography that helped launch her side gig as a photographer. Operating as Super Vintage Party, she shoots concerts and events in the music, drag and alternative arts scene.

“With small businesses you learn how to do a little bit of everything and I like that,” she says of her work with Ekologic. She picked up photography and social media skills on the job and decided to carry it into her social life.

Einbinder began breaking into the Capital Region DIY music scene in 2012, when she could efficiently practice the craft and start to grow an audience. Photography made her more comfortable talking to subjects and taking up space in the community.

“It was something I was doing quietly. I have a ton of anxiety and the camera became a way to become a conversation starter,” she says. “I tell everyone, DIY gigs are a great place to practice photography because, for one, it’s not as restrictive as your regular gig at, say, Upstate Concert Hall. It’s very flexible. Two, chances are, no matter what photos you take, the bands are probably gonna like them or want to see them.”

Einbinder spends almost every day shooting shows or editing photos when she is not working her full time job. She’s amassed a little over 800 followers on Instagram account. She’s not too worried about growing her side gig, as her 9-5 takes precedence. She rarely feesl pressured to meet photo deadlines; it’s her passion project for the love of the community.

“I’m sure that everyone would say this, but I bet if I were more organized I would be more successful,” she says. “But I’m OK with the slow build. I can do as much or as little as I want…You learn to make choices.” .

Photography does little to supplement her income; Einbinder estimates that roughly 75 percent of the work she shoots is free.

“I maybe make an extra $50-100 per month, depending on what kind of work I’m doing,” she says. “With the DIY bands, it’s really hard to profit—almost damn near impossible—from the culture because these bands are working off of almost no funds.”

To offset that, Einbinder has begun freelancing and selling merchandise, prints and zine booklets. She accepts payment from bands who ask her to shoot a live show, has shot album covers for artists (like Albany singer songwriter Gracie Lineham) and has recently been offered pay to shoot music videos for local bands. (Editorial note: Ariel Einbinder is a frequent contributor to The Collaborative magazine.)

Einbinder encourages others to go for their passion if they have even a sliver of time to explore it.

“If that interests [you], please do it,” she says. “The beautiful thing about photography is that everybody sees something differently and I think you can apply that to really anything—everyone is going to have a different perspective and you will influence in your own way.”

Entrepreneur Eugene O’Neill, 27, works full time at his fashion and screenprinting business Made In Truth Clothing in Troy. He also maintains side jobs as a creative consultant and arts education consultant, working program- or event-based gigs such as the September Stitched fashion show in Albany or the springtime Albany Center Gallery sponsored project Corner Canvas, helping students create murals for vacant downtown properties. He also works with Albany schools, teaching private art lessons and developing art programs.

Photo: Kelvin Zheng

“I think I’d probably be in a lot better situation if I was just focused on one [job],” he laughs. “But I was compelled to do them all because even in creating art for people every single day, there was a point where—for years—I didn’t create art for myself. So that right there is why I need all the other ones. They keep me active. I try to be well-rounded. I want to work on what I’m not good at.”

O’Neill has been working with screen-printing and graphic design for the past six years and still considers himself in the first stages of his creative career. “I think it takes five years to do anything in trial, when you’re just doing it for the first time,” he explains. “I think it takes 10 years to really realize what your direction is.”

Only about 5 percent of his monthly income comes from his side work.

“All the jobs are still currently in progress,” he says. “I feel that certain things had to be learned to make a platform for these other things to grow. They don’t support me yet but I’ve been at them for five months, six months. By a year they will.”

One of the most important lessons he has learned was to plan for eventual returns on his investment. With so many projects in the works, O’Neill’s financial plan is laid out with the knowledge that what he puts into a job won’t necessarily come back to him immediately.

“What I learned was not only how to create opportunity, but how to scale it,” he says. “You have to know who’s consistent. I think over that time I’ve built a relationship with a lot of clients so that I know what’s working and there are no surprises. I guess the pleasant surprises daily would be like the clients that get me new jobs [through word of mouth], my business is built on that.”

Like Einbinder, O’Neill has found time management and organization big hurdles in managing his many roles, particularly when it comes to balancing his business and creative needs. He’s considered hiring an executive assistant to keep him accountable, but has managed so far by using apps like Google Calendar and Monday, a team management and communication software.

“It’s like plates you stack really high for a long time and you just have to keep holding them as an endurance thing,” he says. “That’s the tough step: How far do you grow in a side gig to think, ‘Wow, I could either give one up or get someone on board to make the side gig bigger.’ Do you grow your team or do you remove one thing and double your time so you don’t have two halves of yourself?”

The “two halves” perspective fits Portia Melita, 23. She believes that her side gig as a freelance graphic designer over the past two years has helped her stay creatively engaged at her full-time job as a barista at the Albany coffee shop Stacks Espresso.

“Some of the design stuff has just been relentless hours because I had to teach myself everything,” she explains. “I spend all of my time outside of work trying to learn all of it and get it done. It’s been worth it though because I thought about doing design or art as a full-time job, but it’s so hard to make yourself be creative for that long—especially when you can’t do whatever you want.”

Melita has worked on full branding packages for business start-ups and handwritten fonts that help her pay about three months in rent. Leftover income adds up to something like a one-way bus ticket for a day trip or a night out with friends. She bought an iPad and an Apple pencil to do more precise design work and jokes that she has “probably made almost nothing” after buying materials.

“If I averaged it, every other month it would be about $100 or less,” she says. “This one job I did included fonts, logos, a neon sign, graphics and I got a whole month’s rent from it, which is amazing but I had to basically treat it as a full-time job for months. I set my pay and made sure it would push me to be creative. The more I’m doing for other people, the more training I am using to do something for myself.”

She relies, passively, on social media to grab the attention of potential clients, but has become more confident in her work, advocating for new projects with every job she completes. “I’ve been more comfortable lately suggesting things,” she says. “It’s hard to market yourself, to know if you’re right for something and I think there’s a lot of that in art.”

Melita feels committed to working in the arts, especially in the Capital Region She grew up here, left and returned, and she hopes her generation of up-and-coming artists will push more boundaries and create a more challenging arts community.

“I’ve had better success when I know a bunch of people who are doing a similar thing and we’re all in this together,” she says. “Albany is weird because there’s an arts community but it’s the same graphic designers, the same painters, the same photographers. It’s felt the same my whole life. There isn’t a lot of risk…the art is staying the same because the artists know what is going to make money.”

People also worry about security. “You don’t want to put money in something you’re not going to get back and that’s really difficult,” she says. “Find the cheapest way to do something completely different and go for it because we need it around here.”