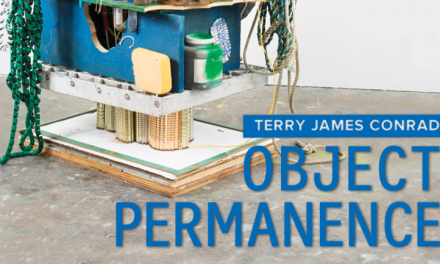

All photos by Richard Lovrich

Traffic on the normally busy intersection of Henry Johnson Blvd, and Clinton Ave. in Albany is uncharacteristically sparse. A few SUV’s with bright Uber lights idle, waiting for the traffic light to turn. The bass rumbles out of one or two sporty sedans; the sound pulses up the utility box, where a man dressed all in black is setting up a large projector.

At over six foot tall with long black hair, a thick black goatee and the frame of a professional wrestler and the aura of a vampire, Samson Contompasis is accustomed to drawing the occasional odd stare or a fascinated long, lingering glance.

Tonight, though, he’s drawing even more attention than usual. With the sun long disappeared behind the autumn night sky, Samson pulls up in his light blue minivan and affixes a projector to a utility box on one side of Henry Johnson, connects that to a MacBook, then carries his buckets of black paint and assorted brushes across the street to a lot littered with condom wrappers and discarded snack-food bags. He takes a long painter’s pole and attaches a relatively tiny brush to its end.

Contompasis sets up a projector on a makeshift shelf. The setup continually draws attention from passersby.

A man with a sign declaring that he is homeless hobbles back and forth down the opposite side of the boulevard, sometimes answering queries from passersby about why there’s a MacBook on the street corner late at night, and why no one’s taken it.

He points over to the hulking Contompasis, who has now begun his task for the night. Its 9 p.m. and Samson is just settling in, tracing the lines of the image he’s projected onto the building–the faces of the street’s namesake, Henry Johnson, and members of his platoon. Johnson served in WWI, and while in France he held off a German raid, fighting and killing Germans in hand-to-hand combat, saving a fellow soldier and in doing so suffering 21 wounds. Johnson, who died poor and essentially anonymous, was awarded the Purple Heart in 1996 and the Medal of Honor in 2015. His name and visage have come to be synonymous with Albany and Arbor Hill, but Contompasis laments that many residents have no idea why.

As the night grows later and Contompasis’s brush strokes give life to the faces of the soldiers, a chorus begins to grow from the passing cars. “Who is that?” a bald man shouts from an idling car. “Henry Johnson!” Samson shouts back, smiling. “I thought so! Keep up the good work!” the man responds. More and more drivers inquire, all seemingly sure this is Henry Johnson but wondering who has set out to paint him, and why. Contompasis is happy to take the time to answer. He’s waited over a year to get approval for the project. “I’ve had this in my head for years. These men should be here. It’s his street.”

A crowd starts to gather. A group of teens, apparently live-streaming themselves, address their phones. “This crazy white boy is just out here tagging. Po Po on their way,” one says. “Who that?” asks another. They point at his equipment. “Dude has to be crazy.” But after the novelty wears off they put their phones down and become observers.

Contompasis lights up a cigarette before getting to work on his mural.

Contompasis has a long history in Albany. His family owned a diner in downtown Albany that was eventually leveled when the Knickerbocker arena was built in 1990. He’s played in various hardcore and metal bands and worked as a multi-disciplinary visual artist. He’s fascinated by war and firearms having worked with guns purchased in local buy-back programs, he celebrates battle and venerates soldiers. While also lamenting the gun violence that plagues some of the Capital Region’s communities.

From 2009-2012 Samson was the proprietor of The Market Gallery in Albany, which served as a guidepost, bringing in internationally recognized artists, including taggers and muralists. Many local artists still see it as a high point for the regional arts scene. In 2011, Contompasis both galvanized the local arts scene and caused some controversy with his Living Walls Project, which brought in artists to paint murals across Albany. The project was funded by donations and included property owners, but some saw it as promoting of the illegal act of creating graffiti and others worried that local neighborhoods were being imposed upon by outside artists.

Tonight there isn’t any controversy. Samson is a celebrity. An older couple approaches Samson the way you’d approach the lead singer of your favorite rock band. They gingerly ask if he will pose for pictures with them. They say they lived in the Bronx for years and knew some of the more prodigious street artists from the ’80s and ’90s. They chat for a while. Samson listens to stories about the glory days of street art, and smiles.

Samson doesn’t work at night to avoid people, that is for sure, The less light there is the easier it is for him to see the projection of the men’s faces. He tosses his hoodie over a street light. He contorts his body to avoid obscuring the projection. Each tiny stroke–the crook of a man’s chin, the crows’ feet under a soldier’s tired eyes, the outline of a strand of hair–requires precise physical movements from Contompasis that involves his hands, arms, torso, and legs. The cool fall air also ensures that the paint won’t drip too much. The lines he draws will stay mostly as intended.

Contompasis uses his entire body to make one simple stroke.

“After a night of this I am physically destroyed,” Contompasis explains. My hands cramp up, my back is killing me, but it’s worth it to see this here.”

He plans on working until dawn. “I’ll sleep in late and maybe come back tomorrow night and see what else I can do,” Contompasis says.

A few days later Contompasis is back at it. The already striking mural has taken on more depth. The men’s faces feel weathered, pained, real. The same sign-carrying man walks back and forth watching Contompasis.

It’s even quieter this night. A man in stonewashed jeans, a North Face jacket, and a grey-peppered goatee lingers, silently watching Contompasis work. After about 15 minutes on the periphery, he introduces himself. “Did you used to bounce on Lark Street?” Tim asks. Samson laughs heartily. “Yeah, I did.” The man says he was a regular patron at Cafe Hollywood. “I knew you looked familiar,” Tim says. “I think you tossed me out of there a couple times.” Both men laugh and exchange a hug and handshake. Tim watches and chats with Samson for about another hour.

Samson works in quiet for another few minutes before another man walks out of the darkness. He’s full of questions, though he seems a little standoffish. Samson explains he has great respect for veterans and he believes more people need to know about Henry Johnson’s deeds. The man says his grandmother worked building ships at the docks at the navy yard in New York City during World War II. “She was a tiny little woman, but I have this picture of her and her friends posing in front of this aircraft carrier they helped build,” he says proudly.

“I need to see that. Can you bring that by? I’d love to see it. I’ll be here tomorrow night.” The man agrees. After he leaves, Samson declares “I need to paint that. I need to paint that here! People need to see that. That this city, that the people here were part of something. They need to see what kind of sacrifices they made.”

Samson has a number of art projects he wants to bring to life in Albany, but he needs city approval and that can take a while, and his time in Albany is limited. He spends the winter months in California, and he also serves as a bodyguard for an internationally known metal singer. When that band tours, Samson is on the road for weeks.

“I don’t have room for pain and negativity in my life anymore,” Samson explains. “I don’t have the patience for winter, for cold, for snow,” he explains over dinner at a local Mexican restaurant. He dashes off projects he’s working on: collaborations and ideas emerge at first slowly and cautiously and then in furious spurts. He’s invented a tool for a fellow artist who is trying to continue her work despite a sudden and overwhelming disability. He has scheduled meetings with officials at Albany City Hall about a major new project but he can’t let the cat out of the bag just yet.

Contompasis reflects for a moment during a conversation in Schenectady.

All of this comes under the shadow of the knowledge that Samson will be leaving again for California once the weather changes. He’s tired of the bureaucracy and he wants to create without constraints. What he accomplishes in Albany is essentially in other people’s hands at the moment, and it’s obvious this is unsettling for him.

I ask Samson whether he returns to Albany because of the family he has here or for something else. Why bother coming back if he feels constrained, limited at times by lack of foresight, lack of support for “real, dangerous art.“

He doesn’t miss a beat. “Albany is part of me and it always will be. What happens here matters to me more than anywhere else. There is so much potential here. So much raw possibility that it can’t just be dismissed. I love it.”

And what about his mural of Henry Johnson on the corner of Henry Johnson and Clinton? What if the building collapses, is leveled, is purchased and rehabbed? The work of art although impressive and impactful could disappear faster than it was created. “It could come down tomorrow. I know that. All I want is for people to see it while it is there. That people see those men and think about what they did. I want it to benefit the neighborhood while it’s there. All I can do it is put it up,” Samson pauses. “And I can do more murals in other neighborhoods. That is what I can control as an artist. The rest is out of my hands.”