This article first appeared in The Alt on August 27, 2018.

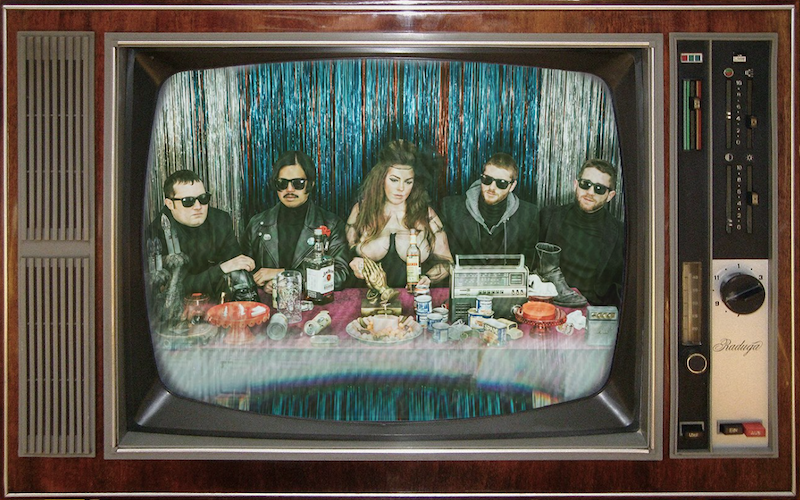

not an Airplane performs at Sofar Sounds. Photos courtesy of Nick Shattell.

“To be honest, my experience with psychedelics really brought me back to music in a lot of ways. I’ve just been riding the wave. Staying devoted to music and starting to come out of my cave to present it. This is the result of that now and I don’t know what will come of it, but I’m starting to get that itch again.”

Meet Nick Shattell, a grinning, bearded man who looks as if he’s perpetually daydreaming. He’s got a deep love of folk music, says he feels it coursing in his blood. He loves it enough to embrace its traditional roots, while turning it on its head to face a new generation. There are further steps to be taken, new perspectives to explore.

Shattell’s folk persona, not an Airplane, once represented the rejection of the internet, a play on an early quirk in Google’s search engine where users needed to oversimplify their queries. Not yet ready for full phrases and questions, “stop words” like articles or negation words like “not” were rejected.

“It was a quirky, punk thing to do but you know, now it’s all about the internet. It never left,” he says. “It accepts the ‘not’ now.”

Shattell talks about the inspiration behind his work the same way he addresses much of anything else: shrugging, smiling, mulling his options.

“It used to have all sorts of meanings. Now I think of it as: I have to drive everywhere,” he grins. “It’s kind of an in-your-face way of saying, ‘Hey, can I get some gas money?’”

The artist has been making albums and touring under the moniker since 2007, taking some time off after his 2013 album Unpredictable Fame. Now, he is set to release two very different albums over the course of a few months. They will be his fifth and sixth releases as not an Airplane.

Still Dreaming of, a new form of lo-fi folk produced by Doug Dulgarian (Jouska, they are gutting a body of water) was released Sept. 5. The first single, “Data Farmer” was released Aug. 22. It’s a stripped down detour from the full band, folk rock sound of his past work.

“It’s much more mature and less certain, because I think with maturity there is no certainty. In my last record, I was very confident that I knew what I was talking about,” he says. “These songs are more like, ‘I’m just a sad man. I don’t have anything for you. Just listen to these pretty songs, hopefully it’ll help. I mean, it’s all I have, too.’”

Songs like “Sad End Stare” and “Remember Tomorrow” are crackling and plucky, the vocals stretching and vibrating like a meditative mantra. Nothing about Still Dreaming Of emotes a sense of urgency or uptick in tempo. Shattell takes his time to play with the tone of his voice, the pronunciation of his words, as if he’s unsure of the next word or idea. Through introspective studies that hinge on self-deprecation, he tries to find a way to make intangible emotions and realizations become solid and real.

“Reflections of loss / Portrayed in the paint / I will plead please take heed of the pain / That is caused for mere personal gain / To satisfy all / Forgotten to think,” he sings in “Remember Tomorrow.”

“When we first started making it, Doug said he was gonna try his best to capture the essence of hanging out with me and I think he did a really good job,” he laughs. “It’s nice to know that those songs have a home now. They never did before, it seemed to almost materialize. It was relieving, for me, because it was like, ‘OK, maybe now I can write about other things instead of thinking about these all the time.”

Some of these formerly homeless songs predate the artist’s entire discography. They’re songs that didn’t seem to belong with any other record, or felt too personal to share with an audience. The newly written tracks play off of Shattell’s recent period of isolation and introspection during his break from music. It grapples with focusing in on the self while intermittently peeking out to interact with the world.

“There’s a lot of loneliness and the heaviness of the social climate in there,” he says. “In my folk I try to be as objective as possible. I obviously try to bare my soul or whatever but I try, in the words, to eliminate the specifics as much as I can so that it speaks to a broader range. It’s harder, the more personal you get, but as you get older you get less objective. There are gonna be people that can never ever relate to my thoughts. That’s what gets us.”

In “CTRL C, X, & V,” Dulgarian captures dreamlike echoes and static. There are interweaving streams of singing, murmuring, rustling, exploring. There’s even a whisper of Shattell’s upcoming hip hop project.

“He really helped me get this edge that I’ve always been looking for but I’ve never known how to make,” Shattell says. “This is the least covered up I’ve ever been. It’s very encouraging. It’s me baring myself as a songwriter. I’m comfortable releasing it too, which is a big step for me.”

For the past two and a half years, Shattell has also been working on the formerly mentioned hip hop album with local musician Joshua “Mirk” Mirksy of the Albany soul and R&B group MIRK. The project, called The Whitest Album, is tentatively set to be released in November and features Albany artists Mic Lanny, DePhyant, Knowle’ge, $waze, Khalil Green, OHZHE, and ELSPHINX.

“We’re trying not to rush it, we’ve spent a long time working on it,” he says. The four 10-to-11-minute track project presented Shattell with a whole new form of artistic collaboration. Instead of operating in a band setting, he was working with a diverse set of artist who brought their own writing into the mix and, for the most part, hardly created anything together while all in one room.

It was born by accident. Shattell and Mirk had only just started jamming together when the folk singer decided he would try his hand at rapping.

“It’s just very lyrical,” he says. “Mirk was the perfect person to try that with, he was super helpful. We made one cool track where I did the vocals and when we started working on the other tracks, I stopped and was like, ‘Hey, these tracks are really good but maybe we should get people who can actually rap to make them sound even better.’”

While Shattell traveled for work around the East Coast and Midwest, Mirk sent him snippets of tracks and sessions he worked up with the Albany rappers in his studio.

“I didn’t even meet most of the rappers. They all brought their A game, it’s a very interesting record in terms of lyrical content,” Shattell says of the project, which he described as politically and socially charged. “I know what it’s like to be a writer without a place to put the lyrics and it just felt good to have this very collaborative, very Albany, record.”

On top of the contributions from the Albany hip hop community, Shattell snuck in snippets of the outside world, like the fascinating (and sociopolitically relevant) introduction to “Warned Free” of a conversation between two arms dealers he overheard at a hotel bar while traveling for work.

“There’s this great clip of him explaining how they buy guns from Russia but have to prove to their lawyers that they’re not from Russia, they’re from Kazakhstan and I was like this is gold! Keep going! I put a little piece of it in the album. It’s so cool how the universe works that way,” he laughs.

The clip jumps right into a fast paced rap, cutting through distortion and beats as a swirling voice repeats “Warning / War is raging.”

‘It add a very human element to it,” he says of the clip. “It kind of makes it a cohesive record.”

It takes a listener out of the project for a moment, but only so far, still maintaining a connection to the artist and their vision: Why did they put this here? Why is it significant? The Whitest Album reads like an epic poem. It’s analytical and far-reaching, making a space for each artist’s style and hopping between them like subway trains. There are plenty of ways to get there, but still one destination.

Ultimately, he decided to call the project The Whitest Album to address his own privilege, particularly as a white male artist. It’s something he struggles to handle, something he wants to use productively.

“I struggle with my job because it feels like I’m taking the easy road when I see all my friends who are musicians and have day jobs but they don’t have an engineering degree, so it’s much less lucrative,” he said. “Privilege is obviously a thing… it’s hard to be like, ‘I want you to hear my music,’ when it’s like, ‘What do I have to say really? I have a good job, I’m white, I’m male, I’m straight, I have nothing to give. I just like to sing.’”

So he turns his creative endeavors into artistic support systems, compensating a network of artists who help him learn more about musicianship, engineering, producing, and marketing his art. As a result, he’s extending his folk styling into different genres, and often, different worlds of people.

“Sometimes it feels like I got trapped inside folk, or that I trapped myself in folk, but it really works,” he says of the genre. “Folk songs are so open to becoming something else, especially when you get other musicians involved. They can turn those simple structures into anything, sonically. There’s so much room. Like, there’s a G chord in this melody, how can we turn it into something that rocks, or has a little bit of funk, or something noisy? I love how much the simple song structure still leaves room for vast ideas.”

During his time touring from the West Coast to the east, Shattell says he has found that folk helps to start a conversation and connection with not only the audience, but other songwriters with whom he has had the opportunity to collaborate.

“I think in the true—Doug called it ‘pure folk’—there’s a rawness to the art form where if it’s done right by me or by anybody, it will always speak to Americans, will always speak to all of us, really, as humans,” he explains. “It’s so true to us, it’s in our blood almost. This raw human emotion and this form of storytelling.”

These connections have helped him change and evolve as an artist in ways he hasn’t expected, like making a hip hop record as a singer-songwriter or his side passion, dabbling in his personal “art music” and noise rock projects such as his role in the Albany duo Fresh Angst.

“How long will people be excited about just me and my guitar?” he asks rhetorically while describing the way his art can stretch and mold. “Maybe I’ll add some more elements. It’s hard to continue being patient, because it’s creation. Our entire culture is: What’s next? What’s the result? Even just sitting on this hip hop record is hard because I want to be able to tell all these people who helped me make it, as well as share it with my small internet community.”

Shattell shakes his head.

“Some people find a format that works for them and stick with it forever and yeah, that’s nice, but we live in a world where pigeonholing yourself doesn’t,” he pauses for a breath. “There’s no excuse for it.”

Still Dreaming Of is available on all streaming sites. The Whitest Album is forthcoming.