Photos by Kiki Vassilakis

To best enjoy this article, first listen to the minute-and-a-half-long song “Composite Character” by End Of A Year. It’s loud, distorted, and not mixed very well, so make sure to also pull up the lyrics and read along. Take a minute to let vocalist Patrick Kindlon’s subject matter sink in, and then listen to it again for safe measure.

Pitching Kindlon’s music to anyone is a supreme challenge because of how vast his catalog is. The Albany-bred Self Defense Family (formerly known as End Of A Year) has released nearly 50 projects since 2003 that traverse post-hardcore, post-punk, post-rock, spoken word, folk, and more. And his other band, Drug Church, who are also from Albany but currently spread between NYC and LA, are their own indefinable fusion of jagged grunge and muscular, though not particularly mosh-able, hardcore.

“Composite Character” is the intro from End Of A Year’s 2010 album You Are Beneath Me and it’s a fitting introduction because it crystalizes many of Kindlon’s most common artistic throughlines into one, straightforward song. Particularly the lyric, “understand art has a context and don’t dismiss things outright.” That line comes shortly after he says, with the same declarative tone, “do not treat retarded people like lepers.”

In 2018, hearing a singer use what is now considered a slur is startling. For some, it may even trigger the knee-jerk instinct to write off Kindlon’s work as out of touch, or even problematic. But those who do a little digging into Kindlon’s personal history will learn that he has a sister who’s mentally disabled, and that he’s worked in human services with people with low-functioning autism for roughly a decade—as he discussed in detail on a recent episode of “Better Yet” podcast.

Understanding the context of art is arguably more culturally relevant now than ever before, and that lyric about outright dismissal could ostensibly be the overarching thesis between the two albums Kindlon released in 2018, Self Defense Family’s Have You Considered Punk Music (Run For Cover Records) and Drug Church’s Cheer (Pure Noise Records).

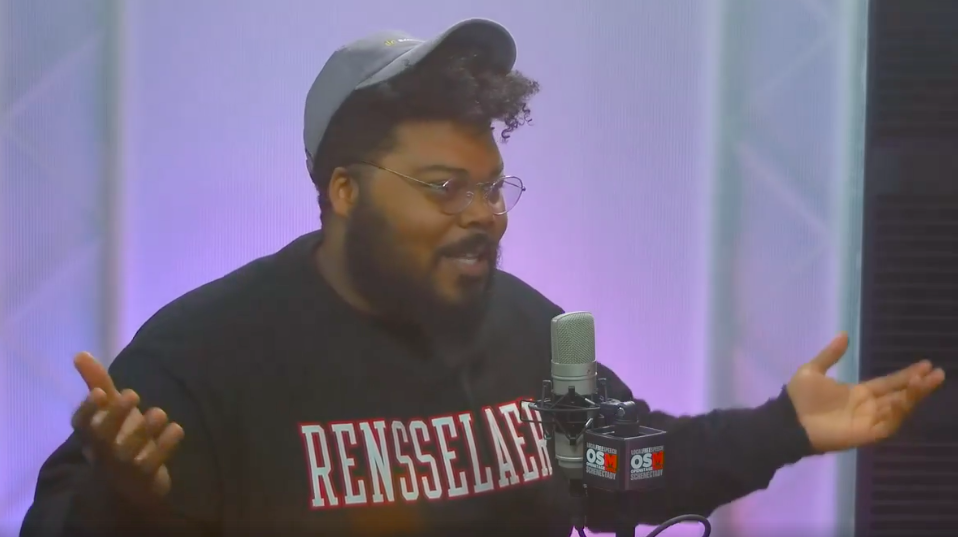

Drug Church in Albany.

“The last five years, maybe, I’ve noticed people attempting not to understand each other at all, but to just get off as many insults as quickly as possible,” Kindlon says during a phone call with The Collaborative in November. “Ad-hoc insults about people’s viability as people based on how they behave, which is kind of not for me. There are pieces of shit in the world, no doubt. There’s no question. Big pieces of shit out there. But I think the kind of thirst to call everybody except for those in our immediate group pieces of shit, is alien to me as an adult. As a kid, made all the sense in the world. But now I’ve seen a lot of things.”

Kindlon, who refuses to reveal his age for the sake of a decade-long bit stemming from an internet forum, grew up in Delmar, NY, a suburban town that borders downtown Albany. He was voted class president of Bethlehem High School, where he was on the wrestling team until he quit when they told him to cut his hair. His father was incarcerated for gambling-related charges when Kindlon was 12 years old, and served almost 10 years. But Kindlon’s quick to say that he has fond memories of his childhood, and that he had a “really, really nice home life.”

“My family is not big into trauma,” he says. “So meaning, I was angry at my father for a year. And then, to me, it’s like—I don’t personally feel wounded by my father going to prison. . .I should say that I missed my father a great deal while he was away. When you know that somebody you care about a lot is isolated and feeling trapped and removed from larger society, that part’s very painful. [But] I was enjoying the fact that I was more or less the man of the house and got to do whatever the hell I wanted.”

His mother, who’d been at home caring for four children, had to re-enter the workforce to make ends meet. But Kindlon remembers, warmly, that he never noticed his family’s financial stress.

“We started getting handouts from the church. And it didn’t really connect with me that that was because we were broke. I just thought, ‘Oh wow there’s a lot of weird ham in the house now.’”

Kindlon started going to hardcore shows in Albany when he was in his teens. He couldn’t play an instrument, so his friends nominated him the singer of a short-lived high school band, and that’s been what he’s reluctant to call his “career” ever since.

Drug Church play the Fuze Box in Albany this past November.

“I’m convinced that for certain types of music, the primary requirement is that you’re willing to fail or embarrass yourself,” he says. “So let’s say that you don’t have access to a good singer, but you know that you want your band to have a singer. The best thing you can hope for is the person who’s willing to embarrass themselves until they get good. And I think some of that is aided by the fact that when I’m singing, I sound good to myself. It’s only when I hear myself recorded that I go, ‘Jeez who hired me? This is atrocious.’”

Kindlon and some friends started the post-hardcore band End Of A Year in 2003. Throughout the rest of the decade, they’d release three albums and a dozen splits/EP’s on hardcore households like Revelation Records and Deathwish, Inc. One of their first shows went down in the campus center at the University at Albany.

“If I recall correctly, we played a room that was entirely too big. I think I fell down? Even though there’s nothing to fall from, there’s just a rug. There’s no stage, nothing to fall [off of].”

But at the turn of the decade, Kindlon, guitarists Andrew Duggan and Chris Tenerowicz, and drummer Alan Huck decided to change the mechanical structure of the band and morph into what would become Self Defense Family.

“We had increasing member changes and instead of being the band that changes a thousand members, we said, ‘Why don’t we change the format of this? Why does it have to be the same four guys? It’s not the fucking Ramones.’ We were still playing hardcore music at the time but we were inspired by, at least in format, folk acts and country acts. Things where membership wasn’t about recognizing everybody as being the original dude. . .where membership is not a revolving door, but maybe there are 12 people you can rely on. And you call each other as needed for whatever the project is.”

That creative ethos has fostered a free-flow of ideas within the group, which has yielded an exceptionally prolific output. Scrolling through the Self Defense Family Bandcamp, which doesn’t even include everything and obviously discludes their loads of unreleased material, is dizzying even for the members of the band.

“I never know what records are out anymore,” Andrew Duggan says from his home in Brooklyn. He’s Kindlon’s longest-running collaborator, guitarist, and one of the band’s go-to sound engineers.

“We had a goal when we first started Self Defense Family. . .wouldn’t it be cool if we start putting out records at this clip, and then in 20 years we go to a record store and we’re flipping through, and we pick up a Self Defense record and go, ‘I don’t even remember this.’ And we managed to do that for me in 10 [years]. I’ll literally go on [our] Spotify sometimes and be like, ‘I don’t know what this is.’ And then play it and be like, ‘I don’t remember playing this, this is wild.’”

Such a discography is freakish for any band, but especially one associated with hardcore, a genre where bands famously burn bright and fast. What’s even more unconventional, though, is SDF’s recording process.

“We sit around, we write a song. Generally in the first or second take,” Duggan says. “[Patrick] pretends to have lyrics for it until we get into the studio and we’re actually paying for the time. And he sits cross-legged in the middle of the room in front of everyone and writes lyrics, more or less off the top of his head. And we all sneer at him and throw shit at him and whatnot. And then he goes in and he does it and we’re all like, ‘Oh fuck. Oh, those are really good.’”

Guitarist Chris Tenerowicz was plucked from St. Rose by Duggan and Kindlon when he was a 19-year-old music major. With very little punk experience, he was recruited for a 45-day European tour in the late 2000s, and eventually became a regular contributor. Today, Kindlon refers to him as one of the group’s primary musical engines.

“Pat has a very good taste for music but he’s also not a very musical person, if that makes any sense,” Tenerowicz says. “He’s the kind of person that knows all the reference points and can kind of tell you if something sucks or not, but he himself can’t really sing, and he doesn’t have rhythm. To some people that might be annoying, but I don’t think anybody in the band is bothered by that at all.”

“He always has something good coming out in the studio, which I appreciate,” Duggan says. “And then when we actually play shows. . .I’ll be honest, it’s very rare he picks up a guitar cabinet and goes down the stairs with it. But he works the room and can interact with the crowd in a way that I don’t really see a lot of people do. So I think it’s a pretty decent tradeoff. To carry a guitar amp and we get to do something a little more distinct.”

“His stage presence has always been pretty memorable to me. How he’s talking a lot and engaging and really just goes for it,” says Jessie Pellerin, the current Geographic Information System coordinator (map-maker) at UAlbany, and a dear friend of Kindlon’s for over 15 years. “Taking off his shirt and just talking to the audience.”

Pellerin also plays in the Albany band Kitty Little, and performs regularly with songwriter Jason Martin. She was an early inspiration to Kindlon because she was both enthusiastic about making music, but also focused on her professional aspirations.

“She was really the first person to pull me into the idea that you can be somebody who’s wildly creative and loves music, and also have the wherewithal to work hard at a job and have a dual structure to your life,” Kindlon says. “Because the type of music that we play doesn’t make a ton of money. So you have to manage these parts of your life.”

Even though SDF, and now Drug Church, are relatively well-known within their circles (Run For Cover and Pure Noise are two of the hottest labels in indie-rock and hardcore, respectively), Kindlon’s still had to hold a litany of odd-jobs over the years to stay afloat.

“I’ve only been financially secure for maybe a few years of my adult life,” he says. “I’ve been broke most of my adult life. So for me, I’m not scared of broke. I’ve got friends right now where if they lose their job or are fearing an upcoming financial crisis, they’re all nervous. And I really never get nervous. . .I don’t care about clothes. I don’t own very many things. So being broke for me is not very scary in the respect that there’s nothing that I particularly want that I can’t have.”

His blase view toward existing in a lower income bracket, coupled with a pervasive air of self-awareness that often leans harder into self-deprecation, is where Drug Church gets its character from. Whereas SDF is generally serious thinking music for chewing and pondering, Drug Church is music for spitting and impulsively doing.

“I call it ‘fall-into-the-bonfire’ music,” Kindlon says. “When I was a kid, people had to find places to party and there was always ‘The Barn,’ ‘Dead Man’s,’ ‘Camp Kaboom,’ ‘Six Feet Deep.’ All these places that are just ridiculous that they have names ‘cause they were just shitholes where people would get hammered, and maybe fall into a fire. . .To me it’s all a pastiche of these ridiculous, ‘Oh did you hear Mark got punched through the wall of a barn?’ All those stupid fucking stories where somebody’s ripping somebody else off for $30 worth of weed.”

However, Kindlon doesn’t sing of these experiences as they are to a high-schooler. He’s describing the party the day after, when all the lights are on and it’s time to shamefully clean up all the puke and broken beer bottles.

“I try not to make it about how cool anything is. It’s more—this sounds corny—but isn’t life really funny? Isn’t it very ridiculous and a lot of these shared experiences that we have are really asinine and really just stupid, stupid things that are funny. And every once in a while there’ll be an emotional beat to those lyrics that I didn’t anticipate, which is another funny thing.”

Cheer, which arrived in November, is the “sophisticated” exception within their discography. Rather than singing about “gas station food and bus station people” and “lifting weights in your yard,” Kindlon’s proposing modern-day cultural criticism about how we behave on the internet. “If you live long enough / you’ll do something wrong enough” is one of its standouts, a notion that few other artists are willing to approach in this era. That is, the guarantee that everyone will inevitably say something offensive or uninformed. And since he hosts a number of podcasts in addition to all of his wordy music, the dude talks a lot.

“If you say a trillion things, you will say something profoundly stupid at some point,” Kindlon says. “And I think that a thing that maybe isn’t understood, by a lot of people, is that law of averages. I am never quick to condemn somebody over something that seems like an aberration. If somebody has demonstrated 10,000 times that they’re capable of saying the right thing, and then they say the wrong thing on the 10,001st time, then I don’t see it as a larger reflection of their character. I don’t see people as their worst moment or their best moment. I think that there’s got to be an averaging.”

The range of adjectives Duggan, Tenerowicz, and Pellerin use to describe him—savvy, honest, distinct, insightful, talkative, enigmatic, polarizing, and “kind of a dickhead”—provide a pretty decent sample to pull from.

“People love to think of him as outspoken. I don’t really get that vibe,” Duggan says. “To me, outspoken means that you’re liable to kind of go off on someone. Where is, I don’t think [Patrick] would say anything he hasn’t considered in some capacity. He’s not just talking out of his mouth.”

“It’s funny because I’ve definitely had to defend him a lot through the years,” Pellerin says. “People seem to have problems with him and he just doesn’t care and I think that’s what bothers people. He just doesn’t really care. He has his opinions, and they’re thoughtful opinions.”

“I think people kind of see him as a funny, dickhead internet troll,” Tenerowicz says. ”But what’s harder to see about him, and I think kind of the reason that we’ve been friends for a long time, is that he’s very selfless in certain ways. . .I remember [when I was 20], being like, ‘Oh I don’t have enough money for the ticket to Europe.’ He just paid it. It was like $630, or something like that. And at the time I was like, ‘Oh the band has money.’ But like, definitely not, now that I know. No band has money.”

What makes him such an individual is not that he’s nuanced and multi-faceted. His point is that everybody is. It’s that he’s one of few rock musicians, and even fewer hardcore musicians, tackling class-consciousness; tender issues like sex work and incarceration; and the often toxic, regressive social discourse of the internet as they relate to tangible experience.

“I think a lot of people believe that by treating people like cardboard cutouts, or like literal, flat, two-dimensional targets—I think that people see condemnation and criticism as a game. . .And I think if we’re going to get really dark, I think there’s people that that might be the only joy that they know. That the only joy in their lives, that I can witness, is the moment that they feel superior to another person.”

Duggan says he’s constantly impressed by how empathetic Kindlon can be toward people who have experiences that are foreign to his. He recalls a time when Kindlon wrote a song about a deceased mutual acquaintance of theirs that left him awestruck.

“He knew him when he was younger as this really bright kid with this bright future, he was really going places and it was working out. And I knew him as the exact opposite. I knew him as, like, a walking cautionary tale. He was the dude who would go to the bar and chug someone’s drink when they weren’t looking, get his ass beat and fall down. . and he wrote a song about this dude that really upset me. The amount of empathy he was able to muster for this kid. It managed to bridge both of our experiences. It was really, really wild.”

Kindlon currently lives in Brooklyn, and hasn’t lived in Albany for many years. When he was coming up in the late ’90s and early 2000s, Ted Etol, who currently runs Upstate Concert Hall, was the person bringing hardcore bands through downtown Albany on a regular basis.

“He really, really made so much of Albany culture at that time for young people,” Kindlon says. “He’s a great promoter. People around the country know him as a really great promoter. I don’t think people in Albany, necessarily, understand how rare it was to have a promoter who made sure that bands wanted to come back. . .Ted, famously, would just walk up to people at the beginning of the show and pay them. And that’s still a rare thing. But back then, for hardcore shows, that was not at all a thing. He really deserves a lot of credit.”

At that time, Kindlon says that there were two thriving hardcore scenes in Albany; the QE2/Valentines-adjacent scene, led by Etol, and the DIY basement scene.

“There wasn’t a lot of crossover, and that’s unfortunate if you look back on it,” Kindlon remembers. “Kids saw themselves as one or the other, and that’s unfortunate cause there was good music coming out of both scenes.”

Ironically, Duggan was someone who came from the basement scene that Kindlon felt isolated from. Which actually makes a lot of sense given SDF’s music blurs the lines between many of hardcore’s minor, yet rigidly enforced, stylistic subtleties.

“The first thing I remember him saying to me, vividly, was, ‘Kids at those basement shows are always so mean to me,’” Duggan recalls. “And I’m like, ‘Alright well cool man, that’s sick. I think I had just had a basement show the day before.’”

Duggan remembers the pointless animosity went both ways, though.

“All the kids who had basement shows would shit on the guys who would go to QE2 shows as being stupid thugs, or pick the adjective you like. And the people who would go to these hardcore shows, when they considered us—which was rarely—it was, like, almost a pity.”

Although many of SDF’s members are originally from the Capital Region, only two current contributors still live there. But Kindlon explains that his decision to leave wasn’t out of resentment toward the area, but because his aspirations exceeded what Albany, at the time, could provide.

“I think places like New York [City] are overrated,” he says. “I think that you can be a creative individual in the middle of nowhere. You can be a creative individual in the suburbs. You can be a creative individual when you’re broke. You can be a creative individual when you’re rich. I don’t know if any of that ultimately is going to stifle a creative spirit. But I do think that certain places can foster one. And I think that Albany maybe not providing what I wanted as a kid, made it so that I wanted to travel.”

“Also, Albany didn’t love my bands. It’s only in the last few years that people are like, ‘Oh you’ve been around a long time, I think I respect you.’ I always had motivation to go someplace else. . .I don’t want to shit on Albany, but I do want to say that by making the thing challenging, it probably made me a little bit better at it.”

Trackbacks/Pingbacks