Editor’s note: Katie Cusack has assisted LaFountaine in the design and layout of “Book of Jayana.”

Jayana LaFountaine knows strong women. She’s been documenting their stories since she started taking photos as a teenager. Most recently, the 24-year-old artist embarked on a project, “Dear Mama,” focusing on the raw reality of motherhood–the challenges, frustrations and heartbreaks such strong women often brush off as “just part of the job.” Although LaFountaine has put this project on hold while she grows her photography business, she notes in a January conversation with The Collaborative that embarking on projects like “Dear Mama” helped her gain the confidence to explore a much more vulnerable project.

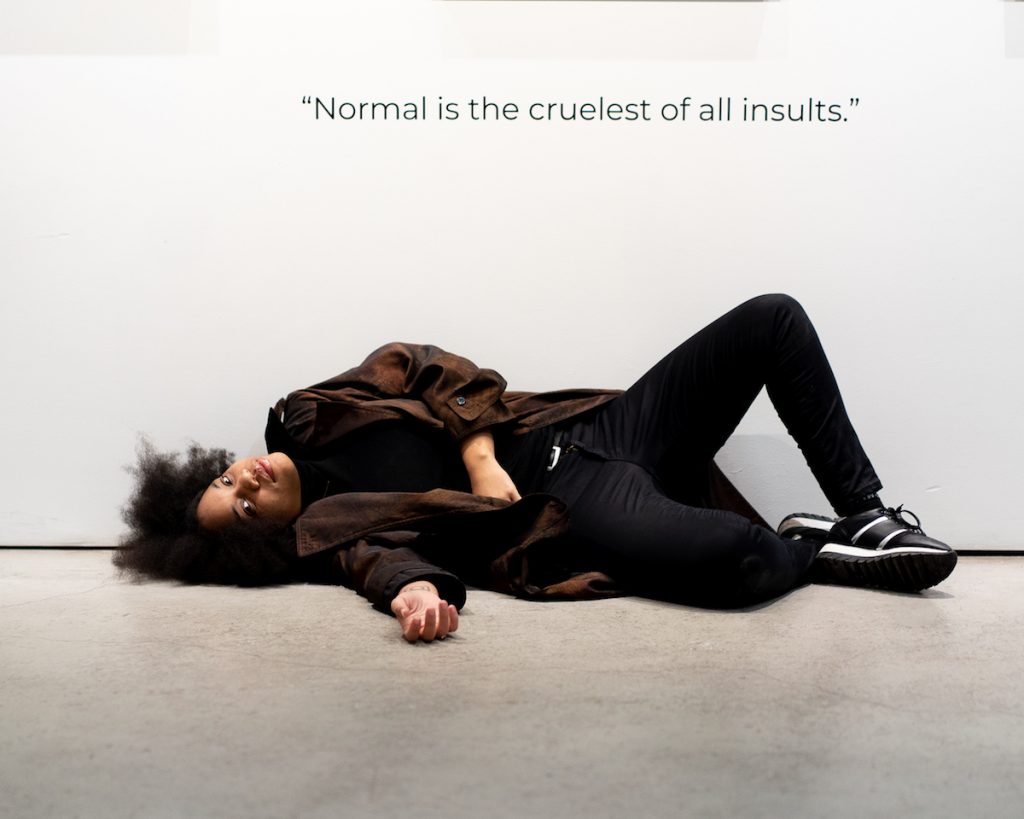

With the preview release of her self-portrait photostory zine “Book of Jayana” in February, LaFountaine–who juggles roles as photographer, entrepreneur, educator, doula and DJ–takes an exhilarating cliff dive: turning the camera on herself.

“It’s an ode to self love,” she says of the project, which she expects to release this spring. “I then want to extend the same opportunity to multiple women so it might be an ongoing project of this collection of beautiful books with women of all shapes, sizes and colors.”

The book has been on her mind for the past four years, stemming from an idea to catalog and present the thousands of self-portraits she has taken throughout her adolescence and young adulthood–the documentation of life and all its cycles, phases and harrowing moments that has become her driving force.

Growing up in the foster care system, LaFountaine didn’t have many photographs taken of her as a child. The photos she carries with her of her mother, father and siblings during their visits are scarce in quantity and limited in quality. They’re faded and tattered, but utterly precious.

After losing her beloved foster mother when she was 13, LaFountaine realized she had few tangible ways to remember the woman who had been such a positive and powerful force in her youth.

“She was my first big loss and every day I think, ‘We should have taken more pictures. We should’ve taken videos, we should’ve highlighted her more, we should’ve done all these things,’” LaFountaine says. “‘Book of Jayana’ is my unofficial therapy for myself. I have a story. It’s an extreme story and I don’t share it often. I share it in pieces.”

In addition to material from her childhood and teenage years, the book will feature more recent explorative, artistic photos that the artist has used to take ownership of herself and her body after experiencing self-doubt, body shaming and abuse. She’s exploring how far she can go, what she can learn about herself. She is vulnerable and unapologetic.

“I have way too many pictures for my own good,” she laughs. “You know how we only really can see something like 10 percent of the ocean and not everything else at the bottom? That’s my photo library. I have thousands of pictures of myself, not in a narcissistic way. I have had issues, just like any other person, with body image growing up in foster homes with other kids who had lighter skin than me. They’d say, ‘You’re not as pretty’ or, ‘Your hair is nappy.’ Those things sat with me for a very long time. When I graduated high school I really embraced my skin and hair and who I really was.”

So she started taking pictures, as if to say, “This is me. Take it or leave it.” It also helped LaFountaine take back ownership of the presentation of her body and sensuality. With control of the camera, she celebrated these aspects of herself and, in a powerful way, eliminated any element of the male gaze.

“[Sensuality] shouldn’t be something we’re ashamed of and I’ve unfortunately had my fair share of assaults. I felt like, ‘This body doesn’t feel like it’s mine.’ So this was also another way to reclaim my body,” she says. “I want to be delicate in my own right. My friend calls me a rose: “You’re pretty but you’ve got thorns.” Yeah, they’re delicate and they can hurt you if you touch it or if you deal with it the wrong way.”

The book will feature a selection of these photos as well as LaFountaine’s recent exploration of modesty–how the concept is serving her in a new different way–as well as a celebration of the purpose she has found in photography.

While her original idea came from a place of trauma, “Book of Jayana” has become a focus on people and journeys. She introduces the world not only to “Jayana” but the people who made her. That includes the presence of her mother, the absence of her father, the strength of her “Mimi” or grandmother, the loss of her foster mother, the teachers who comforted her, the foster care workers that cared for her, the foster parents that did not.

“They can only love you to the capacity in which they can love themselves,” reads a page of the book, a mantra the artist has repeated to herself.

The book will take its readers on a journey from trauma to triumph through the photography that LaFountaine yearned for in youth and harnessed in adulthood. The art form has strengthened her in so many ways, helping archive her life, peek into deeper parts of herself that needed healing and build a professional career she feels she was born to have.

“I think it’s important to tell stories and to pair those stories with media,” she says. “Otherwise, how else do you pass on your memories and your triumphs to your children, your grandchildren, so forth? I have an ear for stories, especially for ones that consist of a lot of trials and tribulations and end in triumph. You’re still here. I’m proud of all those people, they deserve for their stories to be told.”

LaFountaine says that working on “Book of Jayana” has spurred new project ideas. Just as she hopes to dedicate her photography to more women, she hopes to tell the stories of others as well. She also hopes she can build her art to a point where she can make “tangible” changes in her community–putting dinner on the table of a few families with the funds, for example, or supporting another artist’s venture.

“We can get to more human relationships through vulnerability,” she says. “It’s important that we think of others instead of ourselves, step outside of it. Being a black woman and business owner, there are so many things that happen to me that wouldn’t happen to a white male or even a white woman business owner. The whole ‘pull yourself up by your bootstraps’ shit is annoying because not everyone has bootstraps to begin with. Some of us are barefoot, walking on hot rocks that are white supremacy and racism. We’re starting from the ground up and I want to tell those stories.”

Follow Jayana LaFotos on Facebook and Instagram to see LaFountaine’s photography and updates on “Book of Jayana.”

Thank you for your contributions to the world.