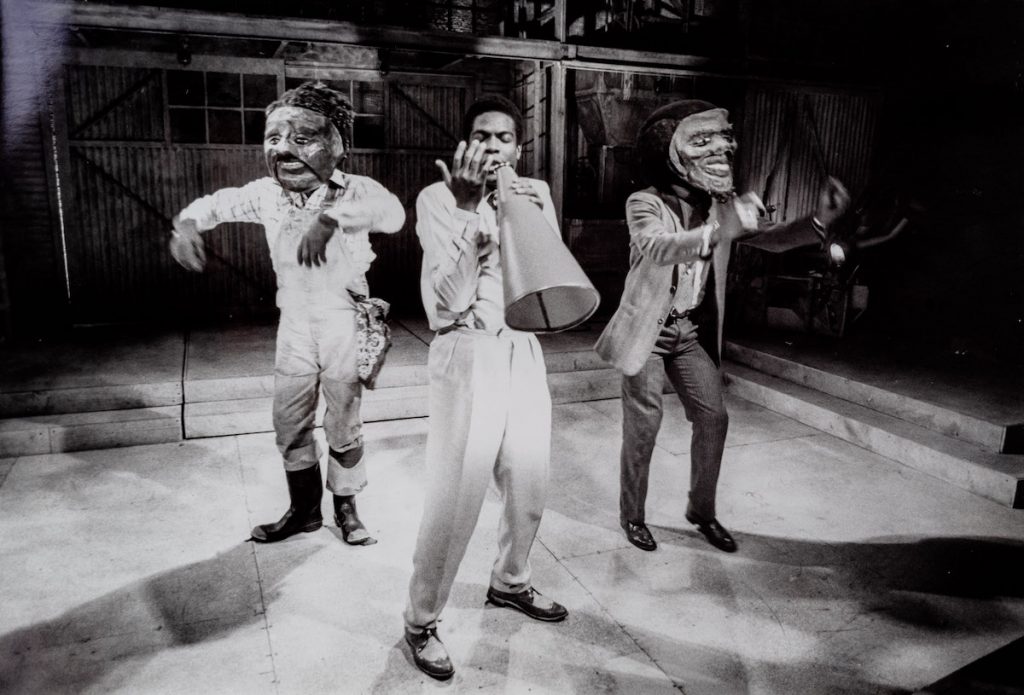

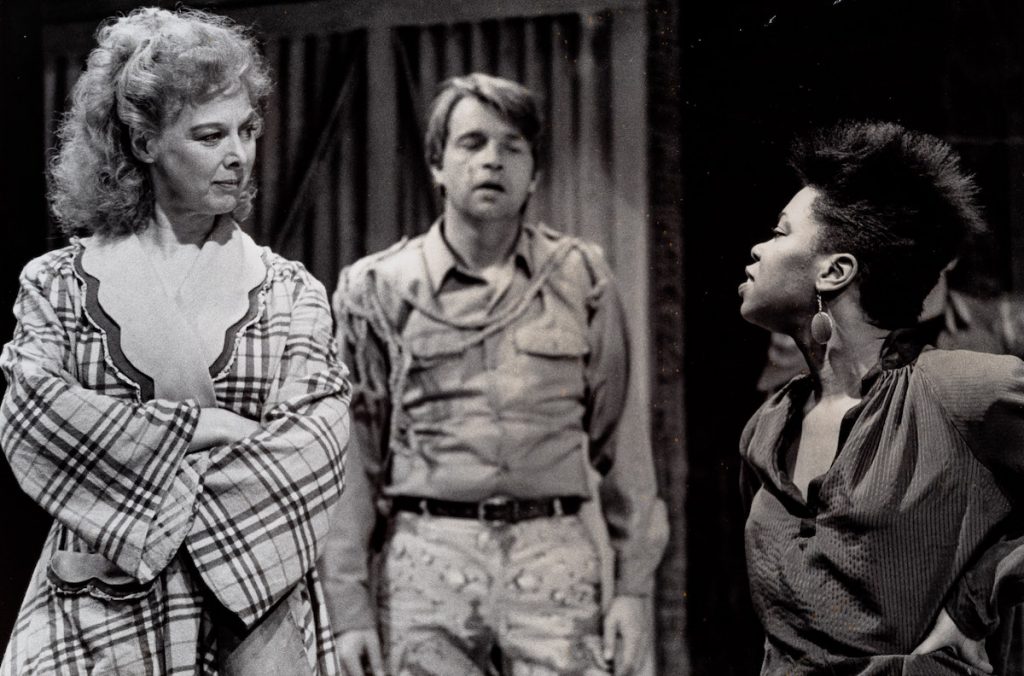

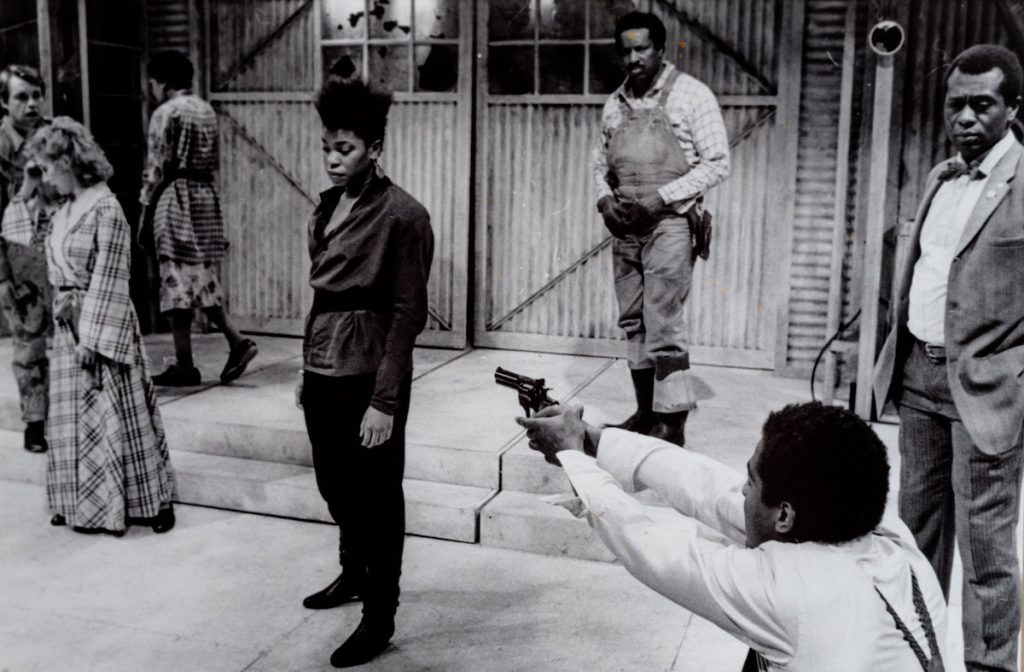

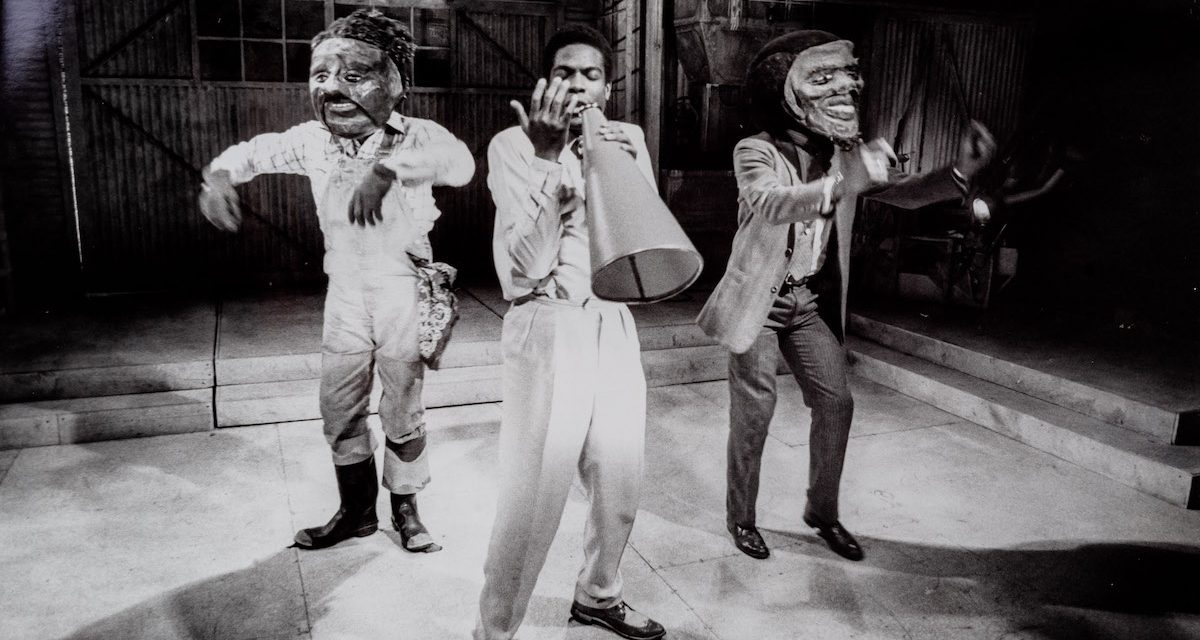

Above: “Dreaming Emmett” premiere at The Capital Repertory Theatre in Albany. Photo: Skip Dickstein

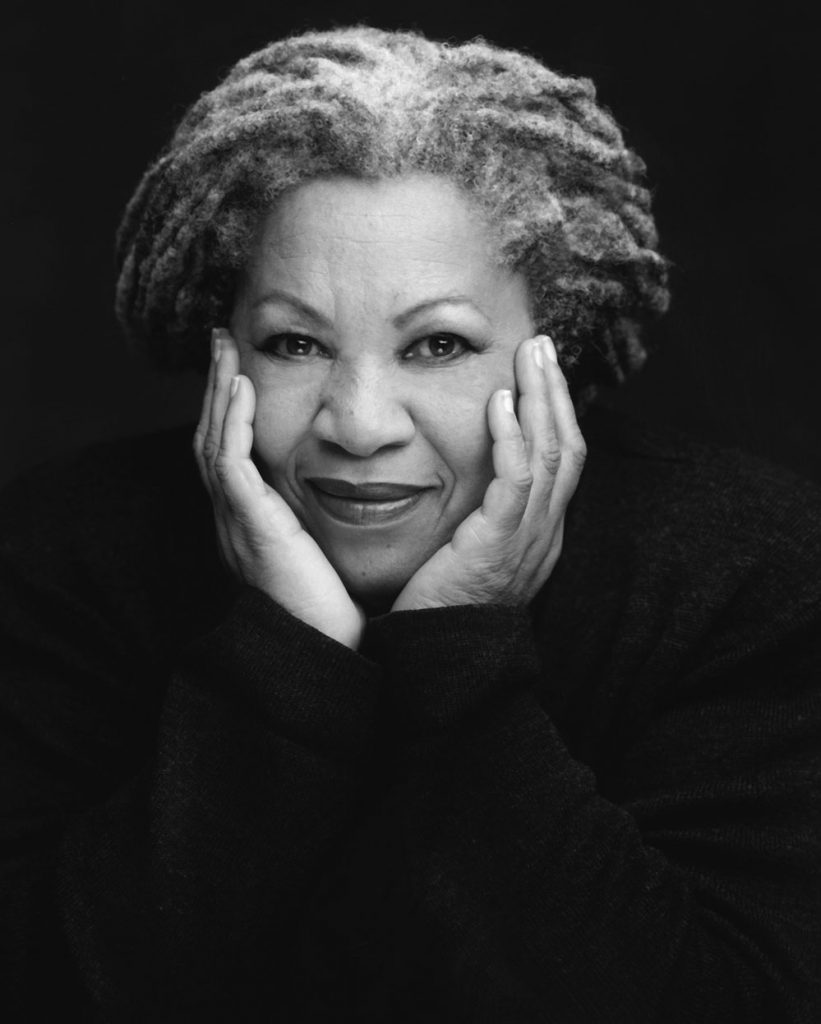

On Jan. 5, 1986, the future Nobel Prize-winning author Toni Morrison premiered her first play at Albany’s Capital Repertory Company’s Market Theatre. “Dreaming Emmett,” based on the brutal 1955 murder of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old black boy, by a group of white men. But after its first run, the play was never produced again. Save for a handful of photographs by Skip Dickstein and a copy of the script (unavailable to the public) held at the New York State Writers Institute in Albany, it all but disappeared. Why?

According to “The Toni Morrison Encyclopedia,” published in 2003, “requests to secure a script from the play have been denied and the play’s producers—The Capital Repertory Theatre—confirm the fact that, after the 1986 production, Morrison collected every record of the play and had it destroyed.”

“Scholars will mention the fact that she wrote ‘Dreaming Emmett,’ but because it never got any traction, we don’t tend to include it in the scholarship on Morrison, in terms of saying what are the features of the play,” says Dana Williams, professor of African American literature, Morrison scholar and interim graduate dean at Howard University.

Morrison, who died in 2019 at age 88, won the Pulitzer for her acclaimed 1987 novel “Beloved”—which she had put on hold to work on “Dreaming Emmett.” In 1993 she won the Nobel Prize in Literature, recognized for powerful works such as “The Bluest Eye” and “Song of Solomon,” which moved the author into the national spotlight in 1977.

The success of this production would have put the renowned author’s new venture as a playwright, as well as the Albany theater where it premiered, on the national radar. In her dream-like reimagining of Till’s life, the murdered teen is resurrected as an adult, summoning and seeking vengeance on his murderers. The play was meant to symbolize the plight of young black men being murdered and overlooked throughout U.S. history.

“There are these young black men getting shot all over the country today, not because they were stealing but because they’re black,’’ Morrison told The New York Times in a December 1985 interview ahead of the play. ‘’And no one remembers how any of them looked. No one even remembers the facts of each case. Certain things were nagging at me for a long time—the contradictions of black people, the relationships between black men and women, between blacks and whites, the differences between 1955 and 1985.”

The show’s four-week run coincided with the inaugural celebration of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday as a national holiday. Looking back at the concept, the dangers faced by young black men that Morrison describes in 1985, when comparing to 1955 ring all too familiar to the violence they face today. Emmett Till. Edson Thevenin. Eric Garner. Michael Brown. Tamir Rice.

When the Times asked her about any concerns leading up to the premiere in ’85, Morrison said, “I know it’s odd. I keep asking Bill Kennedy to find one American who wrote novels first and then successful plays. Just one. And neither he nor I could come up with any one American. Even Henry James was a failure. He tried it three times and each time it was worse than the other. But I feel I have a strong point. I write good dialogue. It’s theatrical. It moves. It just doesn’t hang there. Besides I have Gilbert Moses. And I have great respect for him as a stage director.”

Morrison was the Albert Schweitzer Chair in the Humanities at the University at Albany in the mid-’80s. She worked and wrote in the shared office space of the Writers Institute—which commissioned Morrison to write her play—and discussed the effort of her “Dreaming Emmett” project often with William Kennedy, Pulitzer Prize winning-author and former head of the Institute.

“She was very fearless in everything and certainly in her prose,” NYS Writers Institute Director Paul Grondahl told The Collaborative. “She really took on what, in a lesser writer’s hand, would be difficult to handle or maybe even taboo. She took on a lot of issues around African American history, around violence towards black people.”

One of the few people to see the show in its limited run, Grondahl remembers “like her novels, the language was on a level that feels very rare, full of uncommon power.”

“It was experimental. It wasn’t a standard drama, or plot driven,” he continues. “It was atmospheric and very interior. I think it was the power of the language and the source material, the story of Emmett Till and how he was killed, that resonated. It wasn’t trying to be a biopic. It was its own work of art and very poetic.”

Several theories point to why the play was never again produced. Some speak to discord behind the scenes of the show; others guess that there may have been issues from the Till estate or creative struggles with the author. Efforts to reach the Emmett Till Legacy Foundation for comment were unsuccessful.

Joseph Phillips, who portrayed Till at the age of 23, (and later went on to star in “The Cosby Show” and “General Hospital”) says portraying Till in Morrison’s production was often extremely uncomfortable, intense and moving. He describes rehearsals in which Moses led the main cast in a reenactment of Till’s kidnapping and brutal murder.

“It was terrifying, even though I knew I wasn’t going to die. I remember at a point thinking, ‘I just really want this to stop. I don’t like this practice.’ Then, looking up at the actress who played the white woman who accused Emmett for whistling at her and thinking, ‘Just say it’s not me and this can all stop.’ And she looked down and said, ‘That’s the boy.’ I’m getting emotional just thinking about it because I was thinking, ‘You have the power to stop this,’ and she didn’t. It was a fascinating moment.”

The experience shifted his understanding of people’s actions throughout history—particularly in acts of violence against the black community—and their own understanding of their power. Later, he says, he told this story in a radio interview with Morrison when she began to talk about the influence of “women who say ‘yes’” knowing what will happen to the young men they accuse. It has stuck with him for life.

He shared a story with The Collaborative about his own son who, at 13 years old, was walking around their private neighborhood in California one night with three white friends and kicked a rock that hit a white couple’s wrought iron fence. The husband tracked down the boys while the wife called the police and Phillips, who arrived at the house—just a few doors from his own—to retrieve his son, was struck again by this moment when he was told that the woman had reported “an African American boy throwing a rock” to the police.

He also remembers the moment he fully realized the play was much bigger than the story of one boy.

“We thought it was about Emmett Till and this injustice and racism but, even more, it’s a story about a mother who lost her son to that same type of violence,” he says. “It was like a light bulb moment, a revelation. At the end of the play she steps forward and says, ‘This ain’t Emmett Till. This is my son.’ Her son. Murdered at 14. Shot in the back for stealing a kite. It carries more weight when you realize he’s anonymous. No one knows who he is, no one remembers him.”

Phillips describes the set during this scene: masks lined up behind him, representing nameless, forgotten murdered young black men.

Elizabeth Adams, who published a 1986 research article on the play for the contemporary theater journal Theatre (Duke University Press), writes that the character of Emmett “insistently demands that we answer his question: ‘Am I the last Emmett Till?’”

“It seems to me that it would be something someone would want to produce now,” Phillips says.

He also says he and the cast expected they “were sure to go down to the Public Theatre” in New York City, where so many of the cast and crew had been hired to do another run of the show after founder Joseph Papp (1921-1991) saw the show. Nothing came of the scouting. Phillips had always wondered if he put on a horrible performance due to nerves, knowing Papp was in the crowd.

But according to Bruce Bouchard, co-founder and former artistic director (1981-1995) at Capital Repertory Theatre, who worked with Morrison as a producer on “Dreaming Emmett,” there were rumors that Papp suggested “some very strong artistic direction” to Morrison’s original piece in order to bring it to the Public and she declined.

During a phone interview with The Collaborative, Bouchard called his experience on the project, “without any question, the most difficult time I have ever had as a regional theater producer,” referring to the production experience as “claptrap.”

Bouchard, now executive director of Paramount Theatre in Rutland, Vermont, aired grievances and described creative disputes between the Capital Repertory stage team and the late director Gilbert Moses (1942-1995), who he called “abusive” to the staff and creative team. He noted that at the time of his hiring Moses was known for his work on Broadway success “The Wiz” in 1974, where he was fired “because of a physical altercation that he had with the music director,” leaving director Geoffrey Holder (1930-2014) in his place. Moses was also known for his Tony nomination for “Ain’t Supposed to Die a Natural Death,” (1971) and Emmy nomination for directing two segments of “Roots” (1977).

He also said that financial stress was put on the small theater when Moses introduced thousands of dollars worth of props, such as the large papier-mache masks by New York City artist Willa Shalit used to represent Till’s murderers and the forgotten murdered black men.

“They didn’t trust the elegance of the play… they didn’t trust the imaginative leap of a dead boy coming back to life as a man wreaking vengeance on his tormentors and his killers,” he says of Moses and the show’s set designer. “When that happens, there is a tendency in theater for the directors and designers to load it up with ‘stuff’. I think we spent $2,000 on this custom chair that Emmett Till rode through the smoke and all the multi-colored hallucinogenic [light] effects to step out in his white suit that probably cost $1,500 and was custom made.”

It was these expenses, including an estimated $4,000 steel track running along the 55-foot thrust stage of the Rep to bring Phillips in and out of the dream-like haze, that Bouchard says made the production’s “entire net effect overproduced and underwhelmed artistically.”

Phillips attests that Moses was an intense and divisive director who upset nearly everyone in the production and spent what he had heard was almost a year’s budget on the show during their 10-week rehearsal, tech and runtime.

Bouchard also points to racial tension and challenging power dynamics that he felt weighed on the production. He described himself and the “white board in Albany” of Capital Repertory Theatre facing off with the black writer and director, claiming “ugly overtones of inverse racism throughout the last half of the production process.”

He remembers telling Morrison he was “was one of the first reps of a regional theater in this country where 15 percent of the work on my stage was an absolute mirror image of the community, 15 percent African American—which is what Albany was at that point—and every year, I had a play written by a black author, directed by black author, acted by black actors except for when white actors were needed, designed by African Americans, the whole thing.”

“And I was lauded for that by other members of the minority artistic community, but not Toni Morrison,” he adds.

Bouchard says, writing wise, Morrison “pulled the work into greater coherence, it made sense,” but suggests a larger theater would have been better suited to make the production a real success, although he is glad Capital Repertory got the opportunity to do so.

“She’s a highly poetic prose writer with very dense narratives,” he says to explain the mystery of the play’s shelving. “There’s a giant difference between Toni Morrison’s style of prose writing and writing for the theater.”

“She was the type of personality to not suffer foolishness,” Williams says. “She would have been very clear about her place in terms of her experience and her excellence and would not have a high tolerance for people telling her about things that she could not do, whether that was as an editor at Random House Publishing Company, as a writer of novels or as a playwright trying to develop for a theater.”

Williams points out that Morrison would actually have been more suited to write for the stage. While she never took formal novel writing classes or did other preliminary training before her writing career took off, Morrison did have extensive experience as part of the Howard Players while she attended the university in the early ’50s. She acted, worked stage production and continued to work with the drama troupe when she returned to Howard as a faculty member from 1957 to 1964.

Playwright Owen Dodson, who was an adviser for the Howard Players during Morrison’s time there, had also produced “Bayou Legend,” in 1941 in Jackson, Miss. The work, based on the opera by composer William Grant Still, was about a lynching and must have hit home for the community so close to Till’s hometown of Money, Miss.

“She would have been familiar with ‘Bayou Legend’ and was familiar with the difficulty of trying to put violence on the stage,” Williams says. “It would not at all be surprising to me, for instance, if she said, ‘You know, Owen Dodson wasn’t able to pull this off in 1941. I’m going to try to pull this off myself and see what happens.’”

Morrison’s play tackled more than violence. Between the character’s interactions with his killers, his mother and a young female character named Tamara, the play explored white supremacy, loss, grief and a challenging feminist perspective. Morrison wasn’t afraid to take risks.

The “Morrison Encyclopedia” quotes a 1991 Till biography, “A Death in the Delta: The Story of Emmett Till” by Stephen J. Whitfield, who notes Tamara’s confrontation with Till “condemning the slain boy for ‘his attraction to white women and his indifference to black women’ is delivered in ‘a voice that compels recognition of Morrison’s own.’”

Phillips recalls the powerful scene in which Tamara puts a stop to the overcharged theatrics of the play’s first half with her confrontation.

“Emmett throws this body out into the middle of the stage and puts his hand into it, pulling out the entrails, and there’s a microphone at the end of it. He begins this concert. Instrumental sound comes on as the audience is applauding and then he rips the masks off of everyone. That’s when Tamara, who has been sitting in the audience this whole time, stops the play and says, ‘I can’t take this anymore!’”

The lights go out, and it’s intermission, Phillips continues. “When we come back it’s more naturalistic in the sense that there are no masks, Emmett is gone, Tamara has taken over the stage and Emmett, who was in hiding, comes back out and he and Tamara have this emotional back and forth.”

Williams adds that “Dreaming Emmett” was not Morrison’s only experience writing for the stage. The writer penned the book and lyrics for the 1982 Broadway musical “New Orleans,” the libretto, or opera text, for “Margaret Garner” in 2005 and a reimagining of Shakespeare’s “Othello,” called “Desdemona,” produced in 2011.

“She spent a significant amount of time in the theater, so she would not have even felt like this was a foreign territory for her,” she says. When you think about the work she did, it would have been easier for her to transition to the stage—from her experience at Howard and with the Washington Repertory Players—than it would have been for her to transition to being a novelist.”

For Williams, the mystery of “Dreaming Emmett” could have been that her novel writing career was skyrocketing and took all of her attention. Morrison had “Beloved” on the back burner at the time and her books were building up a significant cash flow and audience. Another explanation could have been that the play, an extremely intense portrayal of the lynching of a black teen and the aftermath of such violence, likely didn’t go over well based on the time period and the audience demographics.

“The story of Emmett Till was not one that anyone was excited to hear about or to sit in the theater and listen to,” Williams says. “It’s one thing to read a book that you can pick up and put down at your leisure. But if you are watching a play that is about the horrors of American identity and racism and white supremacy, when the theater-going audience is predominantly white, it’s difficult to gain a lot of traction, particularly at that time. Also, to have any number of major theater companies try to pick it up and say, ‘We really want to do this piece.’

Grondahl and Bouchard also wonder if, after seeing the work play out, “Dreaming Emmett” didn’t perform to Morrison’s standards.

“She was a perfectionist. My feeling is—just knowing how she revised, revised and revised, so that when you read her books they are just these perfectly polished little gems—maybe she felt this work wasn’t her very best,” Grondahl suggests.

While Phillips agrees some of the stage design, such as the large masks, overshadowed the story, he loved the work and had a great experience with the Albany theater. He even continued to do a play reading series there after “Dreaming Emmett.”

He still has his script from the play, as well as a cast-signed poster and the tail of the kite that led to the violent death of Morrison’s fictional Emmett.

Phillips cherishes the day of his audition—recounted to him in full one day by Moses. He was riding high off his successful first episode of “The Cosby Show,” feeling confident and sure of his performance, ready for a new role. Ironically, his was the only audition Morrison had missed that day, having stepped out for a break.

When she returned, Moses told her, “You just missed your Emmett.”

Opening during Black History Month (February), the Writer’s Institute in Albany will display an exhibit of Toni Morrison archival material available to the public in their Science Library atrium. For more information, visit nyswritersinstitute.org/toni-morrison

Took my mother to see Dreamin Emmett at Capital Rep in 1986. The following year Capital Rep had ‘Fences’. The play of the movie that Viola Davis and Denzel Washington were nominated Oscars for (Viola won). Both Great productions I was born 4 months after Emmett Till was killed in 1955. I didn’t know the story until reading it in EBONY and JET magazine on the 10th anniversary when they printed pictures of the open casket.