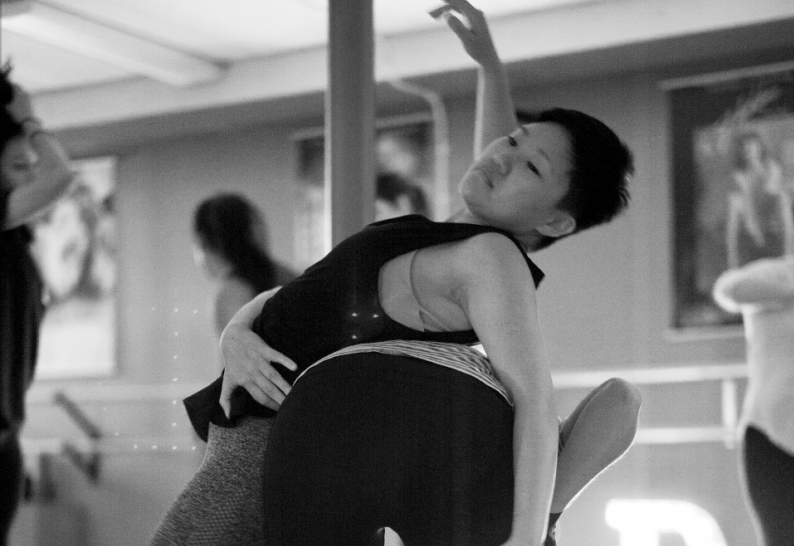

Photo: Richard Lovrich

I’ve struggled with how, when and whether I should write about this but acknowledgement and deep study of my own destructive thought patterns, and the application of strategies to work through them, is a passion. Moreover, it has contributed to growth in dancers I’ve taught in recent years.

We all have deeply rooted beliefs about ourselves. These beliefs stem from comparison to peers, comments received by parents, teachers, siblings and friends or even our work environment. In some cases the feedback happens once, perhaps from a trusted individual or mentor. In other cases the feedback is more consistent, like that of a toxic relationship.

In dance class, beliefs formed from this feedback manifest in ways often disguised as: lack of confidence or effort, inability to look in the mirror or do across-the-floor work, difficulty expressing certain characters needed for a piece, defensiveness at feedback or even being observed, anxiety, tears, inappropriately timed humor, etc. Some of these are so subtle that they’re often overlooked or simply taken at face value, leaving us with a missed opportunity.

In my adult and teen classes, we talk openly about the voices in our head: negative feedback loops that often play out when we quiet ourselves long enough to listen. As a dance teacher, one thing I look for is whether my dancers can sustain eye contact with themselves in the mirror while executing choreography. If not able to do so after making a verbal request to the whole class (singling no one out), I know I potentially have a deeper issue on my hands. These dancers are often the same dancers who will demonstrate defensiveness if given feedback, near crushing anxiety while being observed, immense discomfort or lack of confidence during across-the-floor work and other defensive mechanisms. It’s likely that no amount of just asking them to make eye contact with themselves will solve this, so I have an exercise that we do to start chipping away at the root cause of these symptoms.

It’s important to note that, before you go into any emotional digging, you have allotted the proper time in class to do so and that you don’t try to take on a role you are not qualified to execute. It’s also critical that you not push anyone beyond what they are willing to explore, because if you are unable to pull them back to a safe emotional place or provide the proper tools to boost them up you may be setting your students up for increased trauma.

If you feel strongly that you need to make a breakthrough with your class, that there are insecurities and self-doubt holding them back, you may want to encourage them to listen to their inner voices.

One way I do this in my classes, only when it’s clear that they can benefit from it and that we have created a safe space, is to have them walk up and face mirror. I ask them to, in silence, make eye contact with themselves without breaking their gaze. That’s their only directive. Then I stand quietly and supportively nearby, perhaps gently pacing the room as I watch them in this practice. After a couple of minutes, which can feel like an eternity when making eye contact with yourself, I let them know they can stop. Then, I ask them to answer the following questions silently (I never demand that anyone share after this, unless they want to):

During that exercise, did any voices pop into your head?

What were they saying?

Were they supportive? Mean? Negative?

If they were negative, let’s try to create a replacement thought. For example, if the voice in your head says you aren’t good enough, let’s try to recognize when that’s happening and rephrase it. You might say something new, like:

“I am good enough. I deserve to be here.

I am growing and brave.”

We step away from the mirror after this and bring ourselves back into the room. It’s important at this time to let people share if they want to, so the class can come to their side if needed, learn from each other, and grow together. It’s also useful to let them journal for a few minutes afterward (we provide free journals to all students, which has been a wonderful practice).

It may seem like a small thing but knowing the signs of negative inner-talk, and having a plan to help dancers of all ages identify and work through it, can have powerful and lasting impacts on how successful they are in class. We risk enabling coping mechanisms if we aren’t sensitive to helping our students identify and overcome debilitating shadow-beliefs about who they are and what they deserve, especially in an art form that relies on vulnerability and offers little hiding room.

Nadine Medina is an engineer, owner of Nadine Medina Designs, owner of Troy Dance Factory and artistic director of Synergia Dance Project.