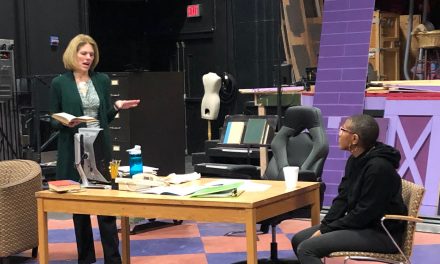

Above: “The Prohibition Project” performed at Collar Works. Photo: Richard Lovrich

The Capital Region is an area replete with traditional theater companies and established performance venues, often competing for the same audiences and entertainment budgets. On any given weekend, one might find no fewer than a dozen different offerings within an hour’s drive of Albany. This has led some in the theater community to lament that no room remains for new artists to emerge. Others have taken an alternate view and tried an altogether different approach: site-specific theater, which brings the craft into unconventional places in order to reach new audiences, bring new attention to overlooked spaces and create new forms wherein the spaces themselves become characters in the stories.

One company created with that mission in mind is Troy Foundry Theatre, founded in 2017 by a trio of artists with the common denominator of studying theater at Russell Sage College. Emily Curro, Troy Foundry’s producing executive director (who was recently acknowledged as one of The Collaborative’s Capital Region Creative Under 40 group) says that the site-specific model was a natural fit for the group’s shared interest in devised theater—a modality for creating work through collaboration and improvisation.

“A lot of the time the venue is where you pull your creativity from,” she explains. “Oftentimes with devised work, that’s all we have in the beginning. We don’t have text, we don’t have a script. The site itself is the start of our story.”

True to its name, the group has focused almost exclusively on Troy, celebrating the city’s rich architectural history by seeking out new spaces for each performance. The approach also allows the group to meet potential new audience members halfway. “We’re really interested in finding ways to connect to nontraditional theater audiences,” Curro says. “So how do you do that? How do you communicate with someone who might not come to a theater because of their preconceived notions? For us, that was ‘Well, let’s bring it to places they would never expect.’”

For NorthEast Theatre Ensemble, whose founder and artistic director Janet Hurley Kimlicko is based in Albany, the focus is on finding ideal historic spaces throughout the region that complement the chosen play. Formed in 2015, the company started in a traditional theater space but subsequently ventured out to produce Lillian Hellman’s classic “The Little Foxes” in the formal dining room of the Ten Broeck Mansion in Albany. Actors performed just inches from the audience, who were seated in the same room. Audience comments on the voyeuristic nature of the experience prompted the group to go all in with the site-specific approach.

“A lot of them told me that they feel like they’re the fly on the wall, almost like, ‘We’re not supposed to be here,’” says Kimlikco.

“Foxes” was a NorthEast Theatre collaboration with director and Siena College theater professor Dr. Krysta Dennis, who had previously used the same space for an immersive staging of her original script on the women’s suffrage movement, “Votes for Women.” Dennis, whose graduate study included guerilla theater done in the streets and subways of London and Paris, is a strong believer in the philosophy that “theater can be made everywhere.” Her long list of past directing credits includes a chamber opera about a suffragette aviatrix that she says was “just too big for any of the theater spaces around”; after her request for performance space was rejected by area airports, she found the perfect fit in a hangar-like Glenville bottle redemption facility built to service aircraft during World War II.

Like Troy Foundry, Dennis views the possibility of working in those kinds of spaces as a tremendous resource; the space serves as a character and a significant part of the experience. “We don’t have to re-create a space, to reimagine a space,” she says. “We can just use it because it’s already there.”

Above: “An Ideal Husband” performed at Ten Broeck Mansion. Photo: Ron Schubin

Creating new rules

At the same time, Dennis says, time must be spent to establish the imagined world of the play for its audience. “You know exactly what kind of world you’re going into when you go into a proscenium theater space,” she explains. “You know that you’ll find your seats, that the usher will help you…it’s very unlikely that anyone will make you do anything, you don’t have to go anywhere… you know the drill.” For site-specific theater, she says, it’s like learning a new language; part of the fun is teaching the audience new rules and seeing if they will accept them.

One typical example is getting the audience on its feet to follow the arc of a story. Techniques might include formal ushering of audience members from room to room, as was done by the servant characters in NorthEast Theatre’s production of Oscar Wilde’s “An Ideal Husband” at Ten Broeck Mansion, directed by Dennis; there is also the full-freedom approach to follow whatever character might capture one’s eye, as was in store for audiences at Troy Foundry’s production of “La Ronde.” For the latter, Philadelphia-based artist and frequent Troy Foundry collaborator Brenna Geffers translated the controversial piece—banned at the turn of the century for its scrutiny of sexual mores between societal classes—from its original German and restructured it for performance within the multiple rooms of the Frear House at Russell Sage College.

Along with the relaxation of standard conventions, of course, comes no small number of challenges. Curro says that Troy Foundry audiences might speak to, or ask questions of an actor. “But we’ve never had a situation where people are purposively disruptive,” she adds. “If an audience member is moved to do something, it’s because of the piece, we understand that and we want to allow them to experience it.” Indeed, the very nature of Troy Foundry’s productions frequently calls for direct interaction between actors and audience members.

Curro adds that the performers themselves need to be “super-malleable,” which the company addresses through ongoing development and training. The ensemble embers works together as a unit, ready to adapt to the unexpected. “Because the audience is so present, you often have to change your traffic pattern,” she explains. “You might have to change the way that you do a scene; your scene might end early because you have to be listening for the scene next to you. It’s a lot of ‘large listening.’”

Safety procedures are put in place just in case anything goes truly awry. For the company’s devised piece “The Prohibition Project,” Curro explains, there was signal that could be enacted “if anyone felt uncomfortable or if an audience member was becoming too physical or too vocal.” Although they never needed to use it, she says “it’s definitely something that we think about when our audience and our actors are so close in space.”

Above: “The Prohibition Project” performed at Collar Works. Photo: Richard Lovrich

Solving technical difficulties

Perhaps the most challenging aspects of mounting a site-specific production are its technical elements. Generally speaking, Curro says, everything needs to be brought in. There’s often a need to build everything on-site, and to find a way to creatively divide the space into an audience lobby, a bar/concession area and the stage itself. There are also production design elements to consider; for “Catastrophe Carnivale,” held in the Troy Gasholder Building, the company needed to do significant re-rigging and re-wiring in order to have stage lights and electricity. The costume designer had to create a wardrobe that could withstand the stresses of performing in a dirt pit. And the cavernous acoustics in the round—which enable sounds from one corner to easily be heard at the corner directly opposite—presented both challenges and opportunities. “Once we were able to control the space in a way that we knew that people would be able to actually hear, we also played with it very purposely,” says Curro.

“We like to look at it as less of a challenge, and more of a puzzle,” she adds. Curro gives credit for that perspective to Geffers, whom she describes as working like a mathematician to create paths for overlapping scenes to seamlessly flow together.

The effort it takes to put the puzzle together also may result in some happy compromises. The first half of NorthEast Theatre’s production of Chekhov’s “Seagull,” held at Mabee Farm Historic Site, was intended to take place outdoors. Ambient noise ranging from passing trains, unseasonably cold temperatures and howling winds, however, prompted a last-minute move into the property’s 18th century Dutch barn. Kimlicko says the adjustment contributed to the audience’s sense of being present with the characters in the play’s remote setting. Sensory perceptions of nearby elements, such as the sounds of live farm animals and the smell of old wood, also enhanced the presentation in a way that simply would be impossible to duplicate on a traditional stage.

Above: “Seagull” performed at Mabee Farm Historic Site. Photo: Ron Schubin

Community response

Kimlicko notes that press given to NorthEast Theatre productions can draw attention to historic sites that otherwise tend to be off the radar. “It’s a win/win for everybody,” she says. “It heightens the awareness of these spaces. People start to hear about them, and come out and actually start to care about them.”

The same dynamic has worked for Collar Works, an art installation gallery space that played host to Troy Foundry’s “White Rabbit Red Rabbit.” The company decided to leave all the art up during performances, widening its exposure to new audiences. “We had people who were still viewing the art at a time when the gallery is closed, people asking about buying the art and people interested in (the) space. They saw what we were able to do with it. A lot of people said ‘I didn’t even know this place was here,” Curro says. She also has seen the symbiosis between performance and place happen in the opposite direction; the company’s audiences have come from all segments of Troy’s diverse community and transcended the limits of what might traditionally be thought of as “theater people.”

When new audience members were drawn to the show at the Gasholder, for instance, she asked how they had heard about the show. They would answer, “We’ve been wanting to see what is in this building for years!”

Moreover, the company’s success has prompted an open-arms welcome from multiple corners of the city. Businesses are donating goods to support the company’s work, venues are working out arrangements to ensure affordability, grant money is being awarded from foundations and governments.

“They believe in what we’re doing,” Curro says. “They believe that we’re making Troy better.”

Toward a new form

While Dennis has frequently created theatrical programming for historic spaces and drawn upon the past for inspiration, recently she has begun looking toward the future with her site-specific work as well. To that end, she has embraced virtual space as another nontraditional stage. Her 2018 creation, “Dutch,” followed a real-life Albany family during the World War I era; a virtual reality simulation filmed with a 360-degree camera on the U.S.S. Slater portrayed a young soldier headed to the battlefield, while live actors portrayed those who remained at their Historic Cherry Hill home.

Dennis is currently looking at various options for incorporating augmented reality into theater, such as having characters appear within one part of a room when viewed through a device such as a smartphone or tablet. She notes that this approach affords the possibility to use a setting such as a battlefield or cemetery to stage a piece, without having to use a large group of live actors on site in a ways that might be challenging or even disrespectful to the space.

Yet if by definition theater must be “live,” one can see why there is some debate as to how such virtual presentations should be classified. “Is it theater?” Dennis asks. “I think so. But I have had many a debate with colleagues (as to) whether or not that is indeed the case—or if it’s another form springing up.” She adds, “I plan to keep exploring.”

Editor’s note: Guest writer Tony Pallone is a frequent collaborator with NorthEast Theatre Ensemble.