Photos by Richard Lovrich

It’s no secret that Proctors heats and cools over 750,000 square feet of downtown Schenectady. But sometimes it feels like it is.

Many longtime subscribers and supporters are aware that in 2005, the stage house at Proctors was greatly enlarged as part of a $42 million renovation and expansion project; that the GE Theatre was created; and that the former Carl Company was converted to Box Office, café and administrative spaces.

Few, though, are aware that as part of the same campaign, Proctors developed and built its own district heating and cooling plant.

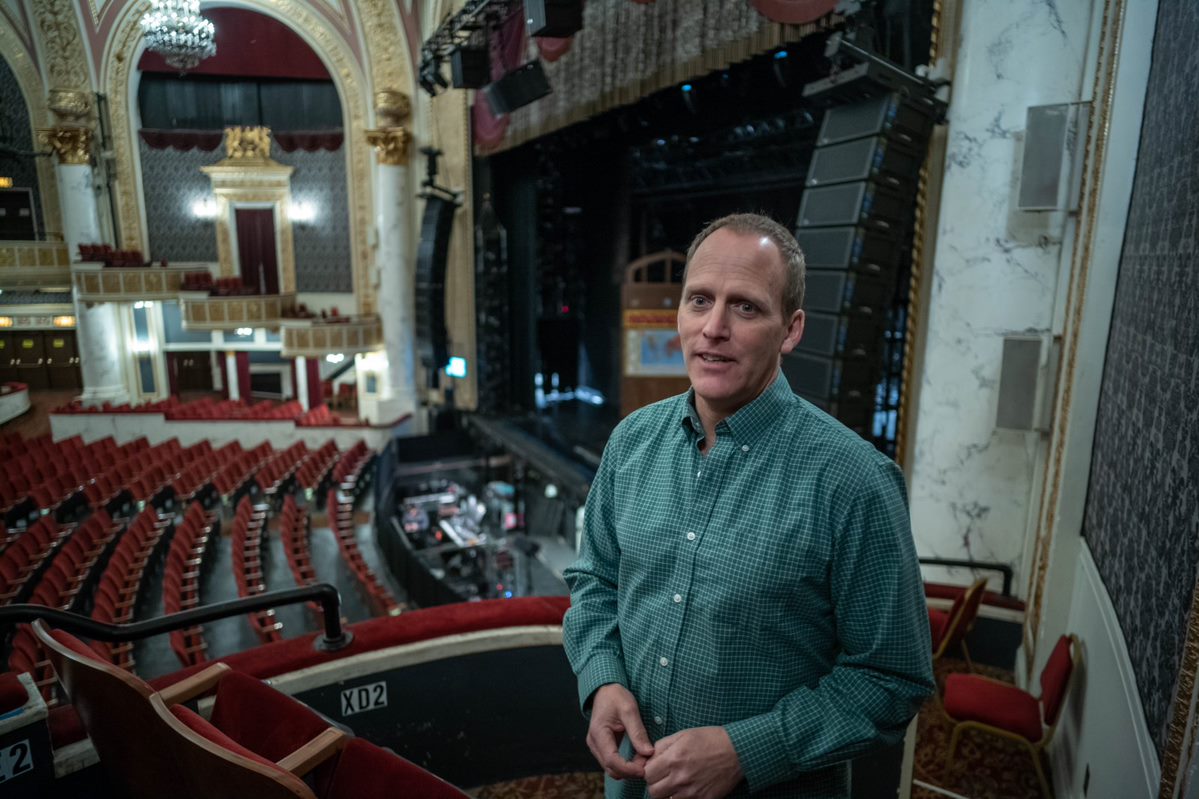

Marquee Power is unique. Proctors is the only theatre in the country that provides district energy to itself and its neighborhood, Elihu Jerabek explains.

Tall, white-haired and laconic, Jerabek, the system’s engineer, mines data for Marquee Power, monitoring operations from a cube situated on the Carl’s second floor, between doors for finance and human relations.

That seems right, since the goal of Marquee Power is to keep folks warm in the winter and cool in the summer, while saving money for all concerned parties.

“Our CEO, Philip Morris,” Jerabek says, “had been exposed to a district energy business back in Jamestown. He had a vision when Proctors was undergoing renovations—why not have a power plant capable of supplying energy for more than just itself. With the economy of scale, a downtown district energy business could provide a lower cost option to neighboring businesses, to the community. It could be done as other things were being renovated in downtown Schenectady, and it would be more efficient than individual businesses with power plants of their own.”

Jerabek speaks like an engineer, referencing heating and cooling “products,” but he thinks like a member of Proctors Collaborative, knowing that Marquee Power, like its pipes that run beneath State Street, is woven into the lives of downtown.

The clear sidewalks along the 400 block, for example; and the ease of passing by Bow Tie Cinemas after an ice storm—that’s Marquee Power’s snowmelt in action.

Those underground pipes lead to City Center. Its dozen or so tenants, big and small, are heated and cooled by Marquee Power. Like the nearby Hampton Inn, which faces the actual power plant, City Center was an early adopter, coming online in 2009. Transfinder and the Parker Inn (which uses only heating at present) are more recent colleagues, gearing up in 2013 and 2015 respectively.

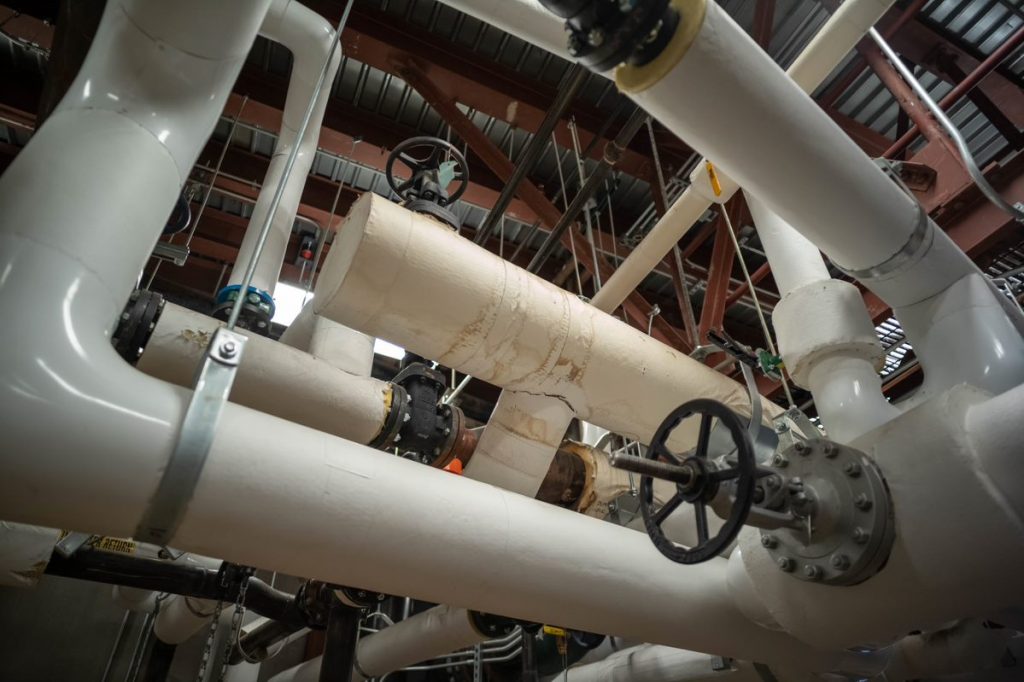

Jerabek and Proctors Facilities Manager Mike Desmond know every bend in every length of pipe inside the 16,000-square-foot facility. They can explain in depth exactly how the plate heat exchangers humming along on the second floor do their mechanical magic. And more.

The entire system is based on water, but not on steam. And Marquee Power’s recipients use their own exchangers to convert the heated (200–220 degrees) or cooled (44–47 degrees) water for use in their own buildings. No potable water is used or produced, but when touring artists, before heading over for a show at Proctors, feel refreshed from a pleasant stay at the Hampton, it’s in part because of Marquee Power—which reduces the area’s carbon footprint by more than 500 metric tons of carbon dioxide each year.

Despite its name, Marquee Power does not generate electricity, but talks and research through a tangle of regulations are ongoing to see if a microgrid might be a future possibility.

With built-in redundancy, Marquee can handle more heating and cooling, if desired.

Jerabek, in trademark flannel and denim, says, “Marquee Power was purpose-built with the foresight of expansion. In addition to having the equipment and the capability to serve our existing customers, we have the capacity to serve more, even with our current equipment.”

The guts of Marquee Power are impressive. In a spring 2014 upgrade, a pair of massive Trane centrifugal chillers, the size of jet engines, were lifted by crane to the second floor, where they now whir with a similar sound beside a smaller rotary screw model. A floor above, a trio of Unilux boilers connected to a maze of enormous pipes and pumps prepare the “product,” essentially BTUs in liquid form, for distribution. Baltimore Aircoil cooling towers decorate the roof.

It could be a stage set for a WPA drama or a revival of Young Frankenstein, if it weren’t so state of the art.

Desmond’s duty within the DHCP is “to ensure we deliver what is needed.” He is also responsible for staff and training, and coordination between service providers and clients.

He knows Marquee Power registers barely a blip on most folks’ screens as they go through their day, warm or cool, depending on the season. He’s OK with that.

“I would compare us to a good, clean, quiet neighbor,” he says, “providing the needed products to ensure our customers are comfortable and confident in their work environments.”

By Michael Eck

Proctors publishes The Collaborative. All content featured in the Proctors Collaborative section is written by employees of the organization.