Featured photo a still from “The Night We Met” a film directed by Jon Russell Cring

Let us set the scene: In the film “Psycho,” we are introduced to Janet Leigh, who has stolen money and is on the run in her sporty, 1957 two-tone Ford sedan. We are offered a shot of her driving, peering into her rear-view mirror. Although the optics offer insight into the

Without the music, the scene might appear lifeless and it can cheapen the quality, making it come off as dashcam footage. In the case of this part of the movie (which you can watch on YouTube) the music becomes the blood pumping through the heart of emotion. Every filmmaker quickly discovers that the wrong music or the absence of its coloration can rob visuals you have filmed of both impact and context.

When I first started making films, I was granted the advantage of my father being a classical composer, so he scored our earliest efforts, sensitive to the story line. But music doesn’t just include the score—there is also a great need for ambient soundscapes and timely inclusion of previously recorded material that needs to be delicately placed into the unfoldings.

Unfortunately, there is a temptation for micro-budget indie flicks to rely on free sites, which only require credit for the use of scores sporting titles like “Darkest Child,” “Carefree” and “Fluffing a Duck.” These offerings are royalty-free and composed by the legendary American composer Kevin MacLeod. Naturally, his work has been used everywhere—from amusement parks to porn movies. It is the definition of formulaic, and some critical souls might say “cheesy.” If that’s what you want and you’re on a tight budget, it can be a one-stop shop to score your film.

When my wife, Tracy, and I had to take on the responsibility for finding music for our later films, we stumbled upon some creative solutions. On several occasions, we contacted regional bands, granting them the opportunity to have their tunes added to one of our creations. Local greats like Super 400, Games Brown and Steve Candlen were also quite excited to create a soundtrack for a budding feature. These musicians marshalled their talent, placing their sound within the movie’s aesthetics.

Perusing Spotify or Pandora has also yielded some great tunes. On occasion, I heard a song for the first time and then investigated the artists. If they own the rights to their material, many are thrilled to be included in an indie project.

But here’s something to remember: If you know the song, you probably can’t afford it.

In an attempt to get around that, I once found a Michigan band who sounded exactly like The Who. On first hearing, you would swear they were brothers-in-rock, and since they recorded their song in the 1970s, it possessed the retro vibe I was going for, without needing to negotiate a huge user fee with Pete Townshend.

I understand that every once in a while, you can become focused on a specific song that needs to be added, so you’re considering getting someone you know to do a cover of it. Good news. Mechanical rights—using a song—cost a fraction of the amount of incorporating the original recording by the original artist.

Although it sounds a bit intimidating, you can find much of the information you need at www.easysonglicensing.com. Maybe it is possible for you to use that perfect song, which possesses the familiarity you desire, but it won’t cost you twice the budget of your entire movie.

Another suggestion: Bandcamp. On our film “The Night We Met,” I discovered dozens of Irish bands that entered a contest to be included in a European music festival. With these contacts in hand, I wrote to them and through the process, ended up getting free music from a dozen amazing Dubliners.

Let’s move on to ambient soundscape possibilities. May I state to you that a drone is basically a drone, and a frog has universal voicings. I would suggest sites like www.Freemusicarchive.org and www.Freesound.org. These will be very helpful in pursuing the cheery or the eerie. I have also discovered that you can find some great electronic sounds on YouTube.

Last, and certainly not least, there’s a treasure trove in symphony recordings. Many local orchestras have released royalty-free performances of top, public domain classical pieces. Bach and Beethoven stand ready to inspire your work with their everlasting melodic magic.

With a little research and a bit of well-placed time, your film can actually sound like the rarest of things: original.

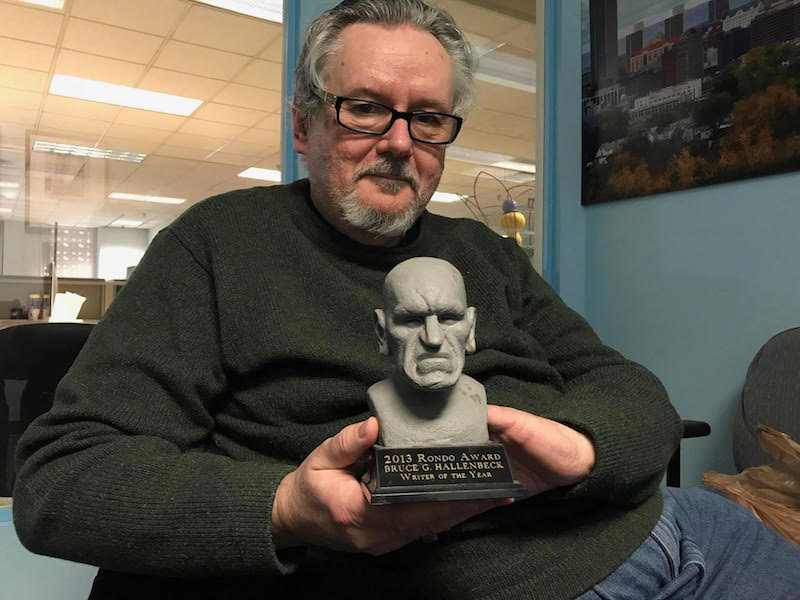

John Russell Cring is a Troy-based director and producer, most recently known for “Darcy” (2017) and “More than Words” (2018).