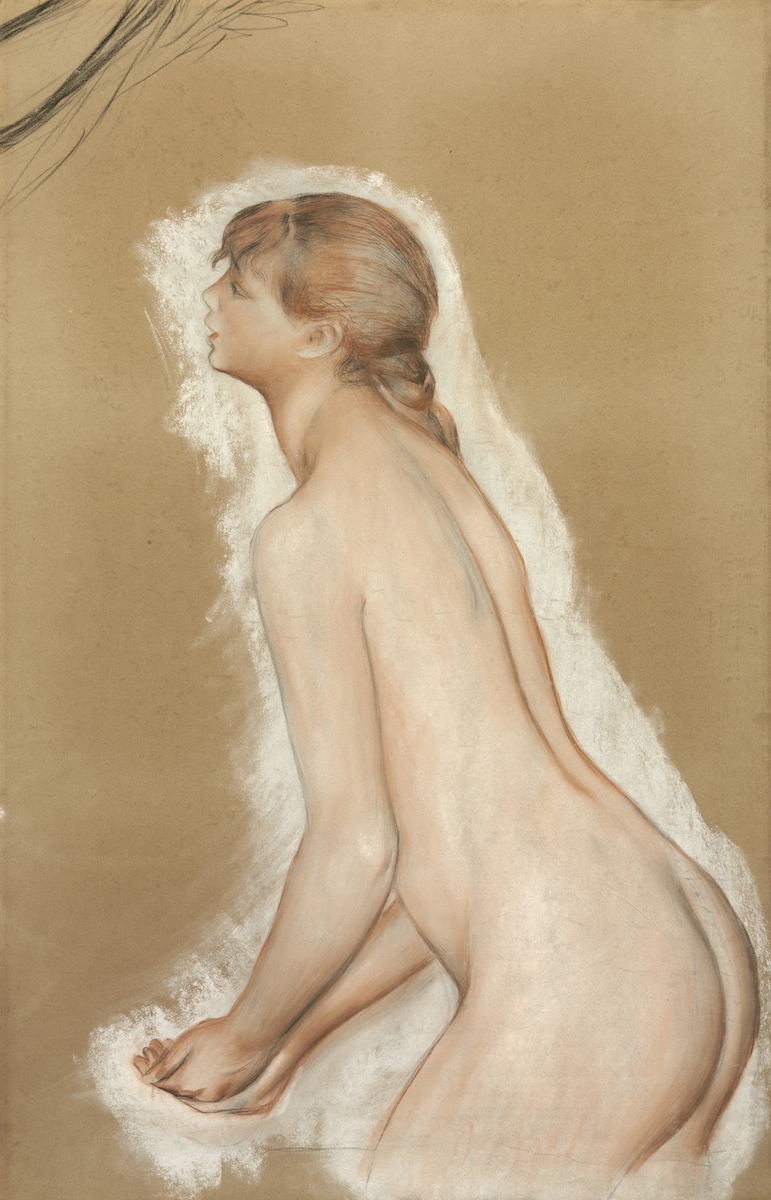

Above: Pierre-Auguste Renoir. “Two Nude Women (Study for ‘The Great Bathers’)” 1884-87.

The Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Mass. opened two summer exhibits in June—“Renoir: The Body, The Senses” and “Janet Cardiff: The Forty Part Motet.” Both pieces represent art forms of such different times, yet both achieve a similar goal: dissecting elements of the same work to peak the curiosity of its audience; to spark attention and better understanding of a larger work.

In an exhibit celebrating Pierre-Auguste Renoir, the classic, impressionist painting style of a legendary artist is unraveled in sketches. His own paintings are placed side by side to compare his development and shifting style and to celebrate his adoration for vibrant color and soft form. The paintings of his predecessors and colleagues featuring similar subject and coloring line the same walls to reveal context and patterns of the time.

Throughout the collection—which features pieces from celebrated artists such as Peter Paul Rubens, Paul Cézanne, Edgar Degas, Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso—the viewer begins to notice the important distinction a bend of an elbow can make, the way a back is bent, the way hair flows down. There is such a significance in the tactile nature of the work that both influenced Renoir and, in turn, his own followers to take care in the placement of a toe, a sightline, a bending finger. Exhibit literature shares that the artist told his close friend and artistic colleague Berthe Morisot, “The nude was one of the indispensable forms of art.”

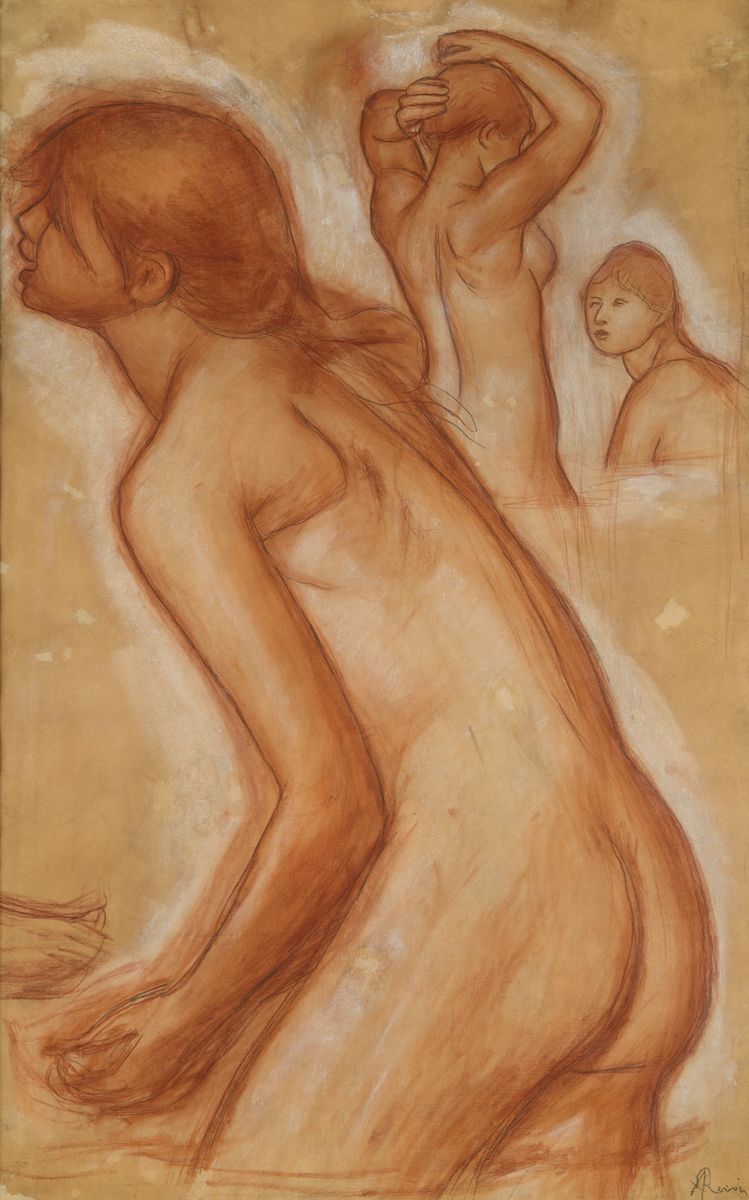

Pierre-Auguste Renoir. “Splashing Figure (Study for ‘The Great Bathers’)” 1884-87.

One room in particular breaks down the very nature of Renoir’s artistic process and devotion to the human form. Following a stint in Italy in the 1870s, where he studied and fell in love with Rafael’s frescos, Renoir dedicated himself to the structure of the old style, entering a period of Classical Impressionism in which he created his great 1887 work, “The Great Bathers.”

Though The Clark was unable to acquire the painting, they refer again to writing by Morisot: “It would be interesting to show all these preparatory studies for a painting to the public, which generally imagines that the Impressionists work in a very casual way. I do not think it is possible to go further in the rendering of form.”

Pierre-Auguste Renoir. “Three Right Figures and Part of a Foot (Study for ‘The Great Bathers’)” 1884-87.

In this collection of drawings, which according to curator Esther Bell “have not been shown together since the ‘90s, not in this way,” The Clark does just as Morisot proposed.

The room offers an exciting glimpse into the work in progress through large-scale preparatory drawings that show Renoir’s more defined rendition of the human body. Figures seem animated, almost vibrating, with the artist’s edits of moved and bent limbs.

Illustrated in bright red and white chalk (and some hints of blue), some exist as works that were sold on their own. Others seem to fit together like puzzle pieces, showing evidence such as a dismembered arm in the corner of the paper.

A view of Janet Cardiff’s “The Forty Part Motet” at The Clark Art Institute.

Janet Cardiff’s 2001 piece “The Forty Part Motet” has come to live at The Clark through Sept. 15, inviting audiences to experience the deconstructed choral work of the Renaissance era, “Spem in alium” (“Hope in any other”) by Thomas Tallis.

The piece was performed by the Salisbury Cathedral choir and additional trained singers in a neutral soundscape, each individual mic’d and tracked in separate channels. Each of the 40 voices contributing to the piece inhabit a single freestanding speaker in the gallery, giving an intimate and deeply moving experience of the piece through the perspective of each singer.

Run in 14-minute loops, the 11-minute piece is paused by three minutes of muffled conversations of the choral group. Speaker by speaker, the listener eavesdrops on children discussing the page they keep getting caught up on, a tenor practicing their scales or the deep, preparatory coughs before the slow, steady humming of the piece restarts.

Upon entering the room and being confronted with the separate, yet unified voices, one could hardly tell whether you have entered at the beginning, middle or end. This is part of Cardiff’s mission to remove the listener from the traditional audience experience, being introduced instead to “music as a changing construct.”

Roaming the circle of speakers, one finds themselves lost in the work. You’re in a different time and place while looking out over the calm pool and rolling hills of The Clark landscape. The deep, rumbling tenor and high, shivering soprano blend and captivate. The medley of voices pull the listener in so wholly that when the piece reaches a moment’s pause, the listener finds themselves holding their breath in the silence.

“Renoir: The Body, The Senses” is on exhibit through Sept. 22. “Janet Cardiff: The Forty Part Motet” is on exhibit through Sept. 15. Visit clarkart.edu for ticketing information.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks